Wonder Woman is the most popular female comic-book superhero of all time. Aside from Superman and Batman, no other comic-book character has lasted as long. Like every other superhero, she has a secret identity; unlike every other superhero, she also has a secret history.

Superman first bounded over tall buildings in 1938. Batman began lurking in the shadows in 1939. But then superheroes got controversial. It began with a gun. On 1 September 1939, Germany invaded Poland. Two days later, Britain and France declared war on Germany. In the October 1939 issue of Detective Comics, Batman killed a vampire by shooting silver bullets into his heart. In the next issue, he fired a gun at two evil henchmen. When Whitney Ellsworth, DC Comics’s editorial director, got a first look at a draft of the next instalment, Batman was shooting again. Ellsworth shook his head and said, “Take the gun out.”

Superheroes weren’t soldiers; they were private citizens. And so, late in 1939, one of Batman’s writers drafted a new origin story for him: when Bruce Wayne was a boy, his parents had been killed before his eyes, shot to death. Not only did Batman not own a gun; Batman hated guns. Hating guns is what made him Batman.

Batman’s new backstory tempered his critics, but it hardly stopped them. On 8 May 1940, the Chicago Daily News declared war on comic books. “Ten million dollars of these sex horror serials are sold every month,” wrote Sterling North, the newspaper’s literary editor. “Unless we want a coming generation even more ferocious than the present one, parents and teachers throughout America must band together to break the ‘comic’ magazine.”

Twenty‐five million readers requested reprints of North’s article, in which he’d called comic books “a national disgrace”.

In June 1940, Germany conquered France. Much of the comic-book trouble had to do, by then, with Superman. Comic books would “spawn only a generation of Storm Troopers”, the poet Stanley Kunitz predicted in Library Journal. In September 1940, the New Republic published an essay called “The Coming of Superman” by the novelist Slater Brown. “Superman, handsome as Apollo, strong as Hercules, chivalrous as Launcelot, swift as Hermes, embodies all the traditional attributes of a Hero God,” Brown wrote, but, he added, in Germany, “it is not the children who have embraced a vulgarised myth of Superman so enthusiastically; it has been their elders.” Time magazine would eventually ask the question: “Are Comics Fascist?”

In the heat of the controversy, a young magazine writer named Olive Byrne pitched an article to her editor at Family Circle – how better to explain to American mothers whether or not comics were dangerous for children than by an interview with Dr William Moulton Marston, internationally famous psychologist? Marston had worked his way through Harvard by writing screenplays for silent movies. He’d invented the lie detector. He’d been a lawyer and a scientist, a novelist and professor. Mostly, in the 1930s, he’d been out of work.

Byrne – who used the penname Olive Richard – was more than Marston’s interviewer: she lived with him. They’d met in 1925, when she was at Tufts University and he was her charismatic psychology professor: they’d fallen in love. He was already married, to an ambitious lawyer named Sadie Elizabeth Holloway. But Marston and Holloway were enamoured of the era’s ideas about free love. So was Byrne: she was the daughter of Ethel Byrne, who, inspired by the British suffragist Emmeline Pankhurst, had gone on a hunger strike after she was arrested, for distributing birth control, in 1917. Ethel Byrne and her sister, Margaret Sanger, both nurses, had opened the first birth-control clinic in the US, in 1916. Sanger’s lover, the British sexologist Havelock Ellis, advocated the “erotic rights of women”. So when Olive met Marston and Holloway in 1925, she was already long steeped in what scholars call the era’s sex radicalism. The three agreed to form a family, with, as Holloway later said, “lovemaking for all”. By 1940, when Byrne was a staff writer for Family Circle, she and Holloway had each had two children by Marston – an arrangement they kept strictly secret, to protect Marston’s reputation.

Byrne got the magazine assignment. Her article was published in October 1940. “Do you think … comics are good reading for children?” she asked Marston. Mostly, yes, he said – they are pure wish fulfilment. “And the two wishes behind Superman are certainly the soundest of all; they are, in fact, our national aspirations of the moment – to develop unbeatable national might, and to use this great power, when we get it, to protect innocent, peace-loving people from destructive, ruthless evil.”

Superman’s publisher, Charlie Gaines, read Byrne’s article and was so impressed that he decided to hire Marston as a consulting psychologist. Marston convinced Gaines that what he really needed to counter the attack on comics was a female superhero. At first, Gaines objected. Every female pulp and comic-book heroine, he told Marston, had been a failure (which wasn’t strictly true). “But they weren’t superwomen,” Marston countered. “They weren’t superior to men.” A female superhero, Marston insisted, was the best answer to the critics, since “the comics’ worst offence was their bloodcurdling masculinity”. In February 1941, he submitted a typewritten draft of the first instalment of “Suprema, the Wonder Woman”. For an editor, Gaines assigned Marston to Sheldon Mayer, who edited Superman. In a letter Marston sent Mayer with his first script, he explained the “under-meaning” of the story: “Men (Greeks) were captured by predatory loveseeking females until they got sick of it and made the women captive by force. But they were afraid of them (masculine inferiority complex) and kept them heavily chained lest the women put one over as they always had before. The Goddess of Love comes along and helps women break their chains by giving them the greater force of real altruism. Whereupon men turned about face and actually helped the women get away from domestic slavery – as men are doing now. The NEW WOMEN thus freed and strengthened by supporting themselves (on Paradise Island) developed enormous physical and mental power. But they have to use it for other people’s benefit or they go back to chains, and weakness.”

It might sound like a fantasy, Marston admitted, but “all this is true”, at least as allegory, and, really, as history, because his comic was meant to chronicle “a great movement now under way – the growth in the power of women”. Mayer made one change: he nixed “Suprema”. Better to call her just “Wonder Woman”.

What would she look like? Botticelli’s Venus? The Statue of Liberty? Greta Garbo? Marston liked to say that Wonder Woman was meant to be “psychological propaganda for the new type of woman who, I believe, should rule the world”, but neither he nor Gaines seems to have given much thought to hiring a woman to draw her.

Instead, Marston hired Harry G Peter. Peter was 61, an antique by comic-book standards, but one reason Marston turned to him is that he had witnessed the political struggle that women had waged in the 1910s, fighting for the right to vote. Peter drew for the San Francisco Chronicle during the years when its pages closely covered the suffrage movement in California; his wife, Adonica Fulton, was a staff artist for the San Francisco Bulletin. Both Peter and Fulton were much influenced by the American illustrator Charles Gibson; he’d introduced the Gibson Girl in the 1890s. The Gibson Girl wore her hair piled on top of her head. She was wealthy, elegant, fashionable, and full of disdain. Her mouth was pouty, her eyes half-lidded, her breasts heavy, her waist pinched. Gibson’s influence can be seen in Peter’s work and in Fulton’s early drawings of women, too.

To Wonder Woman he brought experience of drawing suffrage cartoons. In the 1910s, Peter had been a staff artist at the humour magazine, Judge, where, along with the feminist cartoonist Annie Lucast Rogers, he contributed to its regular pro-suffrage page, the Modern Woman. Rogers liked to portray women breaking the chains of their enslavement to men: Peter drew Wonder Woman the same way.

Marston wanted his comic book’s “under-meaning” to be embodied in the way Wonder Woman carried herself, how she dressed and what powers she wielded. She had to be strong and she had to be independent. Everyone agreed about the bracelets – which were inspired by a symbolic pair of bangles worn by Olive Byrne – she could stop bullets with them and that was good for the gun problem. Also, this new superhero had to be uncommonly beautiful; she’d wear a tiara, like the crown awarded at the Miss America pageant.

Marston wanted her to be opposed to war, but she had to be willing to fight for democracy. In fact, she had to be superpatriotic. Captain America, a new superhero, wore an American flag: blue tights, red gloves, red boots, and, on his torso, red-and-white stripes and a white star. Like Captain America – because of Captain America – Wonder Woman would have to wear red, white and blue, too. But, ideally, she’d also wear very little.

To sell magazines, Gaines wanted his superwoman to be as naked as he could get away with. Peter got his instructions: draw a woman who’s as powerful as Superman, as sexy as Miss Fury, as scantily clad as Sheena the jungle queen and as patriotic as Captain America. He made a series of sketches. Then he sent them to Marston. “Dear Dr Marston, I slapped these two out in a hurry,” Peter wrote, sending along sketches, in colour pencil, of Wonder Woman wearing a tiara, bracelets, a short skirt (blue with white stars), sandals and a red bustier with an American eagle spread across her breasts. Marston wrote back, adding his notes to the drawing. Eyeing her bare midriff, he asked: “Don’t we have to put a red stripe around her waist as belt?” Later, it seems, Marston made another suggestion. What if Wonder Woman were to look more like a Varga girl, one of the pin-ups drawn by Alberto Vargas that appeared every month in Esquire (a magazine Marston regularly wrote for).

The Varga girl, introduced in Esquire in October 1940, was long-legged, slender and open-mouthed. She wore her hair down, her nails polished, her legs bare and clothing that was little more than a swimsuit. Wonder Woman, with her kinky boots, looks as though she could have been on a page of Esquire’s annual pin-up calendar.

The Varga girls were just this side of allowable, by the standards of the 1940s. (In 1943, the US Post Office declared that Esquire contained material of an “obscene, lewd, and lascivious character”; Wonder Woman would run into the same kind of trouble.) Peter sent Marston another drawing, in pen, ink and watercolour. Wonder Woman, carrying her lasso, wears red boots instead of sandals, blue short shorts instead of a skirt, a tight-fitting red halter top with white lapels and a belt marked “WW”. As Peter eventually drew her, she was the suffragist as pin-up. A new breed of superhero – and a divisive female icon whose popularity would span seven decades – was born.

But, in a way, Wonder Woman has been around for a lot longer. In 1914, Sanger started a magazine called the Woman Rebel. The “basis of Feminism”, Sanger said, had to be a woman’s control over her own body, “the right to be a mother regardless of church or state”. A century later, what is the state of the rebellion? The child of sex radicals, Wonder Woman is the missing link in a chain of events that begins with the female suffrage, feminism and birth-control campaigns of the 1910s, and ends with the troubled place of feminism today. Feminism made Wonder Woman.

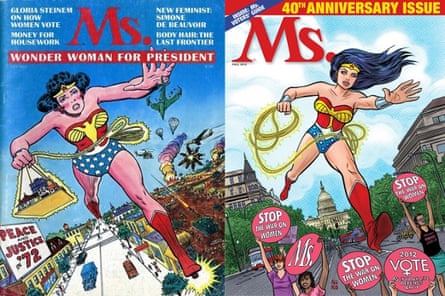

And then, in the 1970s, with the women’s liberation movement – whose icon was Wonder Woman – the character remade feminism. (In 1972, Gloria Steinem and the other founders of Ms magazine chose Wonder Woman to be the cover girl for its first issue; at the end of the decade, she had her own TV series, starring Lynda Carter.)

But this hasn’t been especially good for feminism: superheroes are excellent at clobbering people but they’re useless at achieving equality. Wonder Woman comes and goes. Lately, she’s slated to be included in an upcoming film, Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice, and, in 2017, in her own film, Wonder Woman. It’ll be interesting to see what she looks like, and what she’s fighting for. Wonder Woman isn’t like other superheroes. Her story doesn’t lie within the history of comic books; it lies within the history of politics. Superman owes a debt to science fiction, Batman to the hard-boiled detective. But Wonder Woman’s debt is to the struggle for women’s rights – a story Hollywood has never bothered to tell.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion