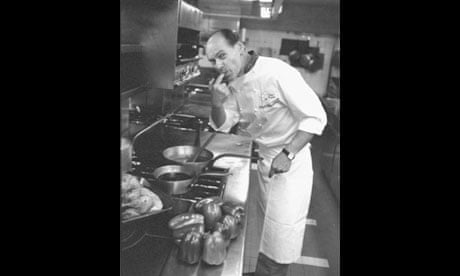

Michel Montignac, who has died of prostate cancer aged 65, was a self-taught weight-loss guru who insisted that diets were never effective in the long run and that losing weight has little to do with cutting calories and taking exercise. "Counting calories does not interest me," he told the New York Times in 1993. "All traditional methods of dieting have amounted to a myth as big as communism and, like communism, are destined to collapse."

The "Montignac method" made him a controversial figure. He explained how he believed his eating plan was different from others: "There is no deprivation and it is not a diet. It is more a lifestyle. It is designed not only to aid weight loss in the short term, but also to help people maintain their weight loss in the long term, by advocating healthy eating habits, which can also prevent illness and disease."

Montignac was born in Angoulême, in south-western France, and grew up in a culture where eating well is central to a good life. However, obesity ran in his family. Both his father and grandfather weighed more than 20 stone (127kg) and, as a young man, Montignac too was obese. After studying political science at university in Bordeaux, he started a career as a manager in the pharmaceutical industry.

Initially he kept his weight under control but, as he explains in the introduction to his first book, Dine Out and Lose Weight (1986), everything changed in the late 1970s when he was appointed to a new post at the European headquarters of the multinational company for which he worked: "I spent much of my time travelling to visit the branches in my territory. These trips were always punctuated with a series of business lunches and dinners, and in Paris, since I was in charge of international public relations, it was my duty to accompany foreign visitors to the best restaurants – not the most unpleasant part of the job."

However, he soon found that he had gained two stone (12.7kg). A chance meeting with a doctor who had a particular interest in nutrition led him to start reading the work of PA Crapo, a diabetes expert at Stanford University, on the effect of carbohydrates on blood sugar levels after meals. Crapo suggested that carbohydrates with a low potential to increase blood sugar levels could help control diabetes.

Montignac was not diabetic but decided to test Crapo's theories on himself. He lost 30lb (13.6kg) in three months while continuing to entertain his business clients by choosing the foods that he ate carefully, but without counting the calories. ("It was out of the question to limit oneself to a hard-boiled egg and an apple.") Friends and colleagues were intrigued, and keen to know how he had done it. His painstaking explanations led to his first book.

Dine Out and Lose Weight was self-published but became a bestseller, shifting 550,000 copies in France. In the book, he identified sugar as the villain. He asserted that it is not a high calorific intake that adds weight, but the high sugar content in some carbohydrate foods that encourages the body to store unwanted fat. Not everyone agreed. In 1993 Marian Apfelbaum, a professor of nutrition at the Bichat Medical School in Paris, described the method as "a delightful, joyous swindle".

Nevertheless, Montignac became an early advocate of the glycemic index of foods, a system developed by David Jenkins at Toronto University, following up on Crapo's research. This system measures the effect of carbohydrates on blood sugar levels (how quickly certain carbohydrates convert to glucose in the blood) as a way of helping people lose weight. Distinguishing "good" carbs (those with low glycemic levels) from "bad" carbs (with high glycemic levels), Montignac banished potatoes, white bread, white rice and white pasta from the daily menu, while promoting unrefined carbohydrates such as wholewheat pasta, grains, beans and lentils.

The Montignac method is divided into phase one (weight loss) and phase two (stabilisation and prevention). In the second phase, the diet allowed a moderate consumption of red wine, champagne, dark chocolate and foie gras.

In 1987 Montignac published Eat Yourself Slim and Stay Slim, a revised and more populist version of his first book, underlining an overall plan of "no deprivation". This second book enjoyed even greater success and was translated into 25 languages. He published more than 20 books in total.

Bringing into play his business experience, he developed a line of low glycemic-indexed products, based on his method, including energy bars, jams, breakfast cereals and even ready-made meals, all with no added sugar. By the mid-90s he had established what was dubbed "La Galaxie Montignac", with a chain of shops, a vineyard in Bordeaux, mail-order foie gras and chocolate, a magazine, an Institute of Vitality and Nutrition, and a restaurant in Paris.

He is survived by his wife, Suzy; their children, Joseph and Peter; and by three children from his first marriage, Charles, Emeric and Sybille. The promotion of his method has been passed on to Suzy and Sybille.