There is an illuminating photograph of Eikoh Hosoe at work in 1968. His subject is the avant-garde dancer Tatsumi Hijikata, with whom he had collaborated for almost a decade. Hijikata is running barefoot across a field and, just a few feet behind him, Hosoe is leaping in the air while simultaneously pressing the shutter of the camera clasped to his eye. Rather than simply documenting the dancer’s performance, the photographer seems to have joined in the dance.

The image speaks volumes about Hosoe’s fascination with, and immersion in, the Japanese postwar avant garde, as well as his commitment to creating images that constantly challenged conventional notions of what photography should be and could do. For him, it was, above all, about immersive collaboration: the creation of a heightened space in which he attempted to become one with his subject. This idea informed his many creative interactions with Hijikata, the founder of butoh, a form of wildly expressive and physically demanding dance, as well as his most well-known work, Ordeal By Roses, in which he photographed the controversial Japanese novelist, actor, dramatist and ultra-nationalist Yukio Mishima, in a series of darkly homoerotic tableaux.

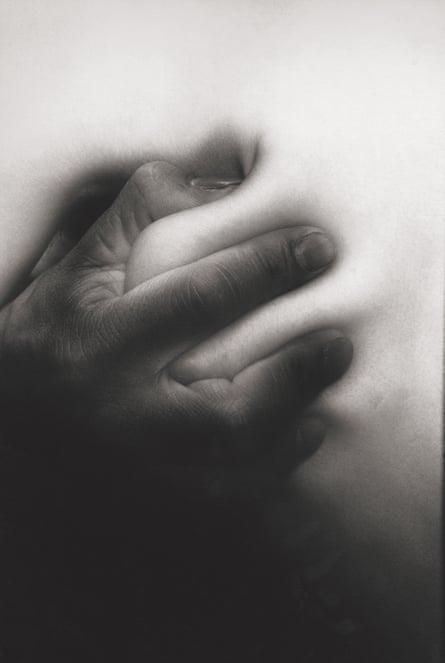

Hosoe was ahead of his time in his embrace of the avant garde and his creation of an often darkly poetic visual expressionism through his use of high-contrast black-and-white tones, sculptural closeups of nude bodies and starkly evocative landscapes that seem to reflect his – and his subject’s – interlocking states of mind.

The boldness of his approach pushed against the parameters of documentary photography, echoing through the work of the Provoke generation of the late 1960s, one of whose leading practitioners, Daidō Moriyama, actually worked as Hosoe’s assistant when he first arrived in Tokyo in 1961. Add to this Hosoe’s co-founding of the Vivo collective in 1959, it’s name taken from the Esperanto word for “life”, and his pioneering photo books, made in collaboration with the best designers of the time, and it is hard not to see him as the most influential postwar Japanese photographer.

Hosoe had witnessed the firebombing of Tokyo in 1944 as a child and his family had been evacuated from the city, living for a time in the village his mother had grown up in. In 1965, he made his series Kamaitachi there, encouraging Hijikata to enact a kind of psychic dance that called up the suppressed terrors of their shared childhoods – including the invoking of a demon weasel that local farmers believed stalked their fields in search of human prey. The atmospheric theatricality of the series did not sit well with contemporary critics or his more traditionally minded contemporaries, who found it indulgent and inauthentic. It now seems audaciously fictive.

In Hijikata, though, Hosoe had found a fellow traveller. Their creative relationship had begun dramatically seven years before, when Hosoe had watched dumbstruck as Hijikata’s company interpreted Mishima’s novel of secret homosexual desire, Kinjiki (Forbidden Colours), in a performance that involved two dancers interacting with a live chicken. He later described the performance as “ferocious”.

“The encounter fundamentally changed Hosoe’s relationship with photography or, rather, the people he photographed,” writes Yasufumi Nakamori, a curator and academic who worked closely with the photographer on a new, meticulously researched retrospective book of his work. “Instead of simply photographing the subject, he began to view himself as involved in the creation of a distinct space and time.”

From that moment on, Hosoe strived to capture the intensity of what Nakamori describes as “the trance-like state” he created through his intense interactions with his subjects. In Mishima, who initially commissioned him to do some publicity shots, Hosoe found an artist willing to lay bare his soul for the camera with an often alarming intensity of purpose. In one infamous portrait, Mishima is shot from above, standing on a circular mosaic of the symbols of the zodiac, wrapped in a garden hose that snakes around his body and into his mouth.

In Ordeal By Roses, they created a powerful narrative that touched on forbidden desire, sadism and ritual, with Mishima later saying that Hosoe’s camera had allowed him to inhabit an inner world that was “grotesque, barbaric and dissipated”, but also shot though with “a pure undercurrent of lyricism”. The resulting book was published in 1971, by which time Mishima had killed himself by seppuku – ritual suicide by disembowelment – an act that lent the series an even darker aspect.

Since then, Hosoe, now 88, has expressed his unease about being too closely identified with Mishima. The new monograph shows how that one famous series fits into a much bigger narrative marked by a relentless imaginative curiosity and a creative fearlessness that took him – and photography – into a new place of uncertain possibilities. Dark, dreamlike and unsettling, his images remain hauntingly powerful in their merging of performance, often intense physicality and an almost mythic atmosphere. Though of their time, they resonate still.