It would be hard to think of an American painter more stinted over here than the Californian master Wayne Thiebaud, poet of the milkshake, ice-cream cone and cherried sundae, of the still life with pie and damn fine cup of coffee. Thiebaud, born in 1920, has been making these radiant paintings for almost seven decades. But in this century at least, Britain has never enjoyed a full-scale retrospective of his luscious Americana, and Tate Modern has no more than a couple of monochrome cakes. So White Cube’s present show is a vital and glorious opportunity.

It is a chance to see Thiebaud’s tiered wedding cakes, twin towers of luminous frosting rising into cool ambient air; and his quintet of cupcakes in their pleated cases, receding into midnight-blue darkness like a row of tiny pavilions. A lone pie slice turns your way, its point sharp as a bird’s beak; a roundel of cheese, one chunk removed, comes in 10 yellows, altered by the ever-changing light. Transfixed by the pristine transparency of the chiller cabinet, the artist paints the interior as a kind of crystalline paradise.

Thiebaud, who worked as a teenage apprentice for Disney, and later at a Long Beach cafe named Mile High and Red Hot (after ice cream and hot dogs), has long been associated with pop art. Overtones of consumerism, mass culture and American plenty – one perfect sundae after another – certainly inflect his work. But it is straight away evident from this show that Thiebaud has more in common with Edward Hopper and Richard Diebenkorn than with pop. His patisserie is so painterly as to imply all sorts of analogies between subject and style. A slice of lemon chiffon pie has exactly that mouthwatering smoothness in its lavish brushstrokes; ice-cream is shapely yet deliquescent, the paint melting ever so slightly as it describes the lush scoop; Thiebaud’s pigment can be as radiant as lemon curd, rich and stiff as royal icing.

Yet this way of painting is also very fully itself, independent of its subject. Sweet as pie though they first appear, these paintings are a more pensive form of praise. Each cone has a subtly different character, invoked by a deeply expressive hand; a patisserie cabinet has the misty blue of nostalgia, a remembrance of days long gone. And you see this, above all, in a beautiful little painting of a salt cellar, one of those soda-fountain shakers with a pierced tin top. Pictured at dusk, all its glass facets shining, it holds the slumped salt within it like a mystery. What started as a still life ends up as a portrait.

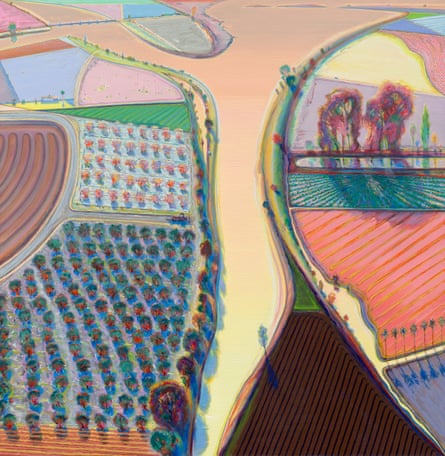

Thiebaud’s joy in America extends out through the landscape, no matter how industrial. Gold and pink striped fields somehow keep their terrestrial reality, despite the celestial colours, because he puts so much exactitude into the drawing that underpins every work. Cars are strung like jewels along highways seen from above, San Francisco hills rise in exhilarating diagrams, and even the fumed darkness beneath a spaghetti junction has its glory – the cobalt of the sky deepening to a potent ultramarine.

The show’s masterpiece is a vast landscape so rapturous it seems closer to heaven than Sacramento. Thiebaud’s emblematic ice creams have now become haystacks in rich Monet hues; and also fruit trees, their cone-like trunks stuffed with blossoming foliage. Each tree casts a blue shadow on the mauve earth, repeated again in the river that undulates away into the distance, a sweep of vanilla, the lemon, becoming tangerine in the serene afternoon sunlight.

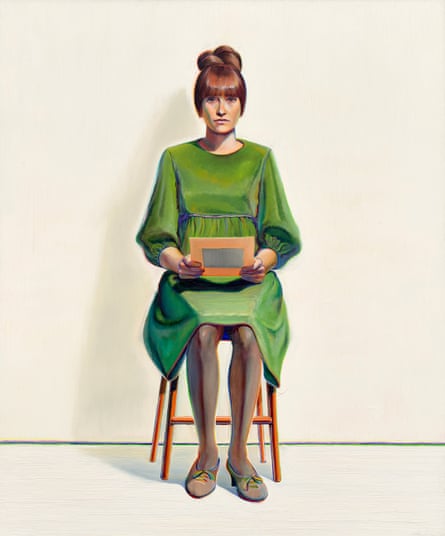

Here and there, at intersections, this vision is pinned together with a nub of condensed colour which then splits into its components – lilac, rose-gold, leaf-green – to cast a fine filigree of shadow at the verges. These gatherings, and disseminations, remind you just how complex an artist Thiebaud is. In a portrait of a woman sitting very still, holding a letter, one sees the same palette used for the shoes in her face, hands, dress and even the letter that dazes her into silence. Who knows what it holds? This is Vermeer translated to America’s east coast.

There is a benign delight to every work in this show, a rejoicing in everyday objects that finds its parallel in Thiebaud’s paint – the way it appears on the canvas apparently alla prima, without underpainting or correction – and in his harmoniously balanced compositions. Each image appears full, solid, complete. Thiebaud has Morandi’s love of forms, glorying in the rhyming ellipse of mug, plate, iced donut and spoon, uplifted into incandescent colour.

But even in all this multiplicity, this safety in numbers – four sundaes, eight cones – Thiebaud reminds you how singular every object really is. An in-tray of immaculately typed correspondence rises to the uppermost letter lying ready, with an airmail envelope, for approval. This envelope is split-new and slightly open as if the world was still open too – the future’s free, the story not over.

A few minutes’ walk from White Cube is another long-awaited show by an American painter, the quiet modernist Milton Avery (1885-1965). Avery is a celebrant too. He loves Connecticut in spring and Vermont in the autumn; the architecture of spiralling firs; the way stands of trees cluster like sheep and cows pattern distant fields like scattered pebbles.

Effulgent in their gorgeous, low-toned palette of greys, mauves, greens and a whole range of pinks that are Avery’s trademark, these late paintings appear modest and even simple – the shapes flattened and nearly blunt, but balanced in the most elegant compositions. A boat on the Thames is described in two bars of pale pink and mint green glowing out of a voluminous black river. The same pink becomes a morning sky in which two numinous oblongs of silver and grey float above a still-dark blue world (Rothko and the abstract expressionists learned from Avery).

Oil paint grazes the surface like a brass rubbing; watercolour tinges the page with delicate light. Each image hovers on the verge of abstraction. Drawings made in summer became paintings in winter – a sense of sustained heat is latent – and even something as humble as a spreading vine acquires a sonorous power purely through the graceful arrangement of its heart-shaped leaves, grey against dove grey against slate, three tones singing together. These paintings have an atmosphere all of their own: heartening, unhurried and beautiful.

Wayne Thiebaud: 1962 to 2017 is at White Cube Mason’s Yard, London until 2 July

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion