How do novelists conceive of whole new worlds in a matter of a few hundred pages? How do journalists approach and capture a tough news story? How does a screenwriter develop plots and characters eventually meant to be seen rather than read? When it comes to the many facets of the age-old art of writing, how a story is told is sometimes a story in and of itself.

In this Shondaland series, How I Wrote It, we’re asking writers of various genres and disciplines to discuss their relationship to their craft and tell us how they tell their stories — through moments of brilliance and creative hurdles alike.

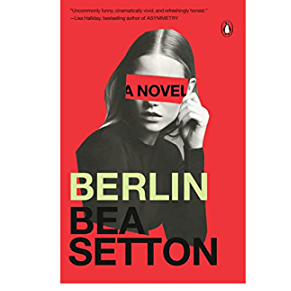

In Bea Setton’s debut novel, Berlin, readers follow Daphne Ferber, a 20-something desperately trying to figure out her life. So, she decides to set new roots in Berlin and in the process navigates the ups and downs of learning a foreign language, the experience of moving to an unfamiliar city, and finding new friends and lovers alike. But one night, everything changes, and Daphne finds herself in what could be serious trouble.

I wrote Berlin at the America Memorial Library in Berlin (donated by America; thank you, America) near the River Spree in the summer of 2019. I always tried to get there close to the opening time because I wanted one of the three coveted tables near the south-facing window.

In fact, on writing days I was so stressed about getting a good seat that I would wake up with a Pulp Fiction-esque dramatic adrenaline gasp at the thought that someone had taken them all. No! No!

On my way to the library, I would bike along the river, and when my bike was tragically stolen one day, I walked, elbows out in case anyone should try to muscle past. When I arrived, if a seat was still free, was a sigh of relief; a silent sulk if it was taken.

Then I would write. I’m pedantic, so I don’t have an interesting creative process. I start at point A and end up at C via point B. I’m even methodical about writing metaphors! How boring. But here’s my method. Though it is not the method, it’s simply my approach.

- Look at the thing you are trying to describe. Really, really look at it. The moon, for example. Forget anything you’ve ever read about the moon; forget anything anyone has ever said to you about the moon. Try to look at it like a child would, as something new. If you rely on old descriptions that others have given you, then you are not connected to the live wire of the moment. And then the writing seems dead.

- Let your mind make all kinds of associations. Does the moon look like a mouth (astonished or screaming?)? A door? A white knuckle? A bald head? An aspirin? The color can look like the white coat of a nurse, or if it’s yellow, it could look like the color of liver failure, or of creamy butter. Or if it’s a very new moon, it can look like a crocodile’s half-closed reptilian eye shining in the dark, a nail cutting, or (if you focus on the point) it looks sharp as a blade, even a scalpel.

- Simultaneously, try to think about the atmosphere you are working to create. So, a milky moon will evoke something very different from an aspirin moon. A knife is very different from an astonished mouth or a nail. The right choice here depends on the atmosphere of the passage you are in.

- Write metaphorically. Send your writing to friends, and ask for honest opinions. They will not be honest, so then you should second-guess whatever they say, and try to read the subtext. Repeat.

Probably one of the most crucial aspects of my process comes down to breakfast, which entails a whole lot of coffee. There is probably a cup of coffee per comma in my novel. Instant coffee is preferable over any of the bougie stuff, but sadly, Berliners don’t settle for that, so I drank unwashed, thrice-filtered Yellow Bourbon, a coffee straight from Brazil. I can’t imagine how much greater this novel would have been if I’d had access to some good old grainy Nescafé.

Then at some point, I would stop for lunch: always the same simit, a delicious kind of Turkish sesame bread shaped like a ring, bought from a stall by the river. In the line for the simit, I would stare at the Berliners all around me. It was important to me that the novel feel concretely grounded in the reality of the city. I wanted people to be able to see it, to taste it, to feel the streets beneath their feet as they read about my protagonist Daphne’s (mis)adventures. Being in Berlin made all the difference; I felt I was watching the novel unfold around me like a film. I would take my simits to a bench by the river and eat them in about two minutes in huge pelican bites. Then I went back to work.

Writing Berlin was not heart-wrenching. It was not agonizing — it was fun. It was one of the happiest and most absorbing and purely pleasurable experiences of my life (don’t worry; book two was agonizing and heart-wrenching and not that fun, so I’ve had my writerly comeuppance). I laughed at my own jokes and cried at my own moments of pathos. The people in the library shot me looks of compassionate concern.

I believe the key to this wonderful experience was because I had no writerly ambitions. I was not considered a gifted writer at school or at university. I once told a career adviser that I’d like to write a novel, and she replied, “Well, that’s nice, but I’d like it if money grew on trees. That’s not gonna happen either.” (She advised me to go to business school to get an MBA.) In any case, I did not — and still do not — think of myself as a “writer.” Writing is a particular activity that I have had the privilege to sometimes do. It is not who I am, and my existence does not depend on it. If you don’t think of yourself as a writer, you can’t be suffering from writer’s block, can you?

The other reason Berlin was so much fun to write was that I did it with my friends. Every time I wrote something I was proud of, I sent it to people. They would send back emojis and GIFs and various signs of encouragement. That’s what I needed at the time — cheerleaders. Not people who would say things like, “Hmm, but I mean, all this pathos, this female suffering, what’s it all for?” and “I hate the protagonist. So unlikable. She’s so unhinged.” This kind of criticism became necessary, but only later. At the start, I treated my work like a baby in the incubator. It needed warmth, love, nourishment, and nothing else.

In a sign of true civilization, the America Memorial Library would stay open until 9 p.m. I’d leave when it got dark, escorted by the friendly bouncer-type librarians. Then I would have dinner with friends at the best falafel place, in a district of Berlin called Neukölln. That falafel is the No. 1 factor in my process — the key to the whole book and creative flow. But that falafel information is classified, so I can’t tell you exactly where it is.

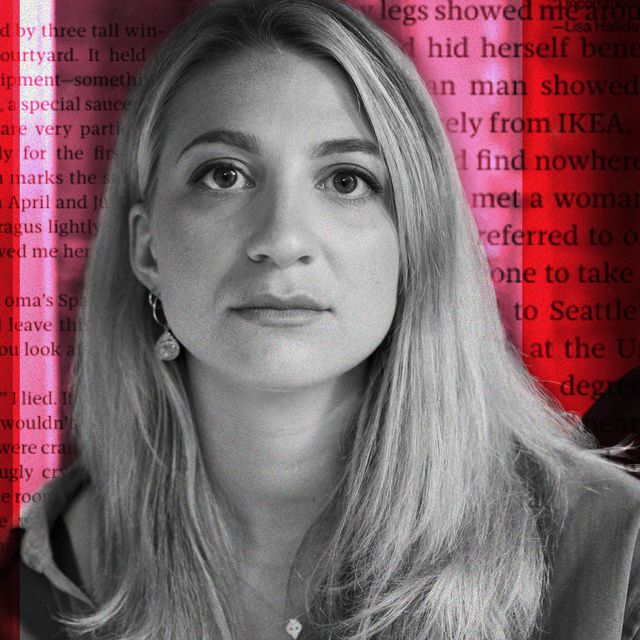

Bea Setton was born in France and spent her early years in the Parisian suburbs before moving to the U.S. to study philosophy. Upon graduating, she relocated to Berlin, and the city became the inspiration for her novel. She currently divides her time between London and Cambridge, where she is studying for a Ph.D. and working on her second book.