They can be seen tearing down the FDR Drive in New York City, wind whipping past as they fill all three lanes with nary a car in sight. They are members of one of New York’s all-Black motorcycle clubs that rule the road throughout the five boroughs.

Peering over their shoulders is photographer Cate Dingley, framing the shot to both capture the scene in front of her and herself in the side mirror.

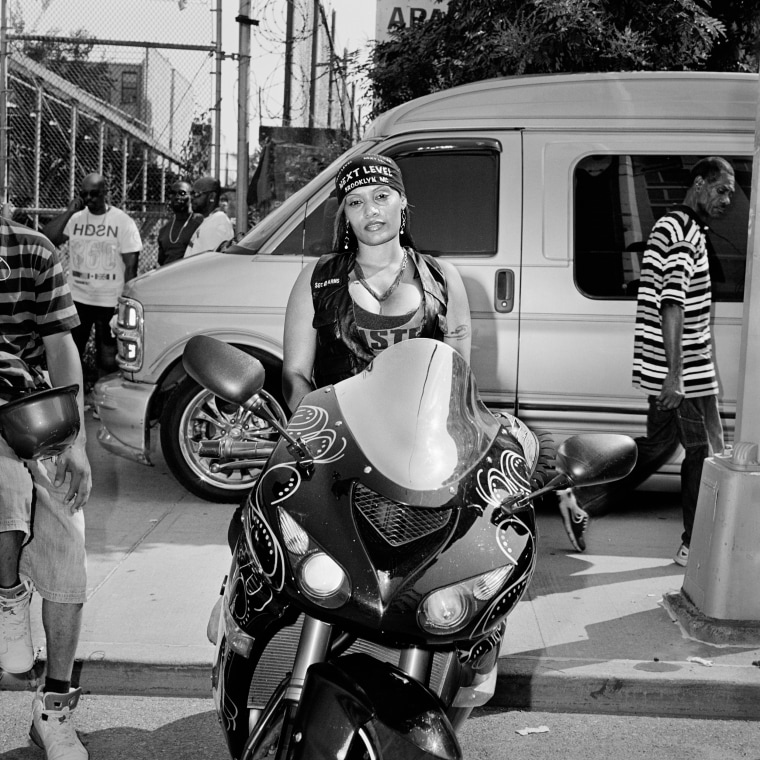

That self-portrait is included in “Ezy Ryders,” a new photography book by Dingley that brings to light a thriving and diverse community with a shared love of motorcycles.

Photographed from 2014 to 2019, the book features black and white photographs from rides, parties, bike blessings, clubs and memorials, interspersed with excerpts from conversations she had with the bikers.

The project grew out of a chance connection through a friend in 2014. Dingley soon found herself making portraits of bikers at a biker club in Bushwick, and she was invited to a barbecue later that day, with hundreds of bikers.

“I had no idea of the scope and scale of the Black MC world,” Dingley said.

She took note of the vast array of vests and insignia representing many clubs — and it wasn’t just riders. Their partners, children and relatives were there, too. The sheer size of the crowd astounded Dingley, and gave her the sense that there was a significantly larger story to be told.

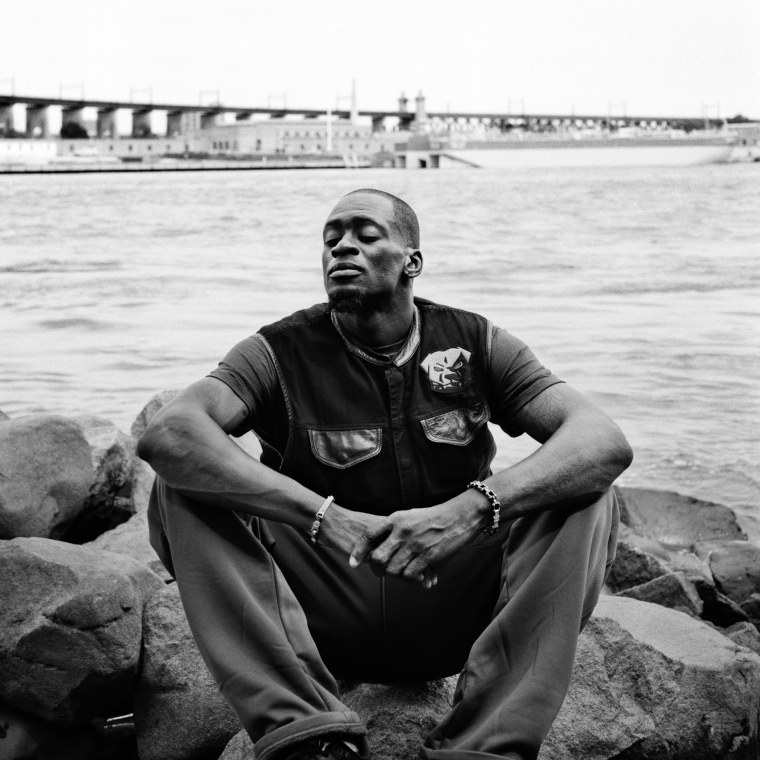

“I would call the Black motorcycle community a very loud whisper,” said Imir Leveque, an independent biker who goes by “Preach” in the community and is featured in “Ezy Ryders.”

Black motorcycle clubs have existed for decades across the country, but they have not historically been well known or popularized outside of their communities. The archetype of an American motorcycle rider has become a white man on the open road, but Black Americans are just as steeped in motorcycle history and culture.

Take the 1969 film "Easy Rider," which cemented the chopper, a custom motorcycle, as an American status symbol. The film made stars of the actors Peter Fonda and Dennis Hopper. Two Black motorcycle designers, Ben Hardy and Clifford Vaughs, designed the iconic, souped-up Harley Davidson bikes — called “Captain America” and “Billy” — Fonda and Hopper rode in the film, according to NPR.

One of the earliest motorcycle pioneers was Bessie Stringfield, who made history as the first Black woman to ride solo across the country in 1930. Her endeavors were not without risks, as she was riding at a time when segregation was the law of the land. Instead of hotels that barred her from staying, she spent her nights in the homes of Black families, or even in gas station lots, according to Iron & Air magazine.

“The Black biker community exists largely because of the racism of the white side,” Leveque said.

In the book, Leveque recounts how he grew up alongside white bikers who proudly displayed swastikas and casually used racist slurs. He rebuked those kinds of bikers by getting a tattoo of a swastika with a strike through it.

In the time she spent photographing the community in New York, Dingley saw that the clubs were often inclusive, welcoming riders from different backgrounds.

Her project, however, was slow to start, as she had to earn their trust.

“You had to prove to people that you wanted to be there,” Dingley said. “I don’t think I was treated any differently than people trying to enter the scene.”

It took a year of consistently showing up to events and fostering relationships before she was fully accepted. The Black Falcons, a club in the Bronx, ultimately vouched for her, signaling to other clubs that she was a welcome presence. After about two years of photographing, she began interviewing riders.

The book flows like an oral history and has the intimate feel of an old group of friends sharing stories at the end of a party, long after most guests have left. Putting their voices front and center was a deliberate choice on Dingley’s part — she knew she couldn’t do right by their experiences any other way. As she photographed, she shared photos on social media, and over time, she would hear from bikers of color across the country, inviting her to come photograph them. While it was gratifying to hear from them, travel was outside the scope of the project.

“I had to narrow my focus to New York if I was to ever do it any justice,” Dingley said.

“Ezy Ryders” subverts expectations both in the people and the parts of New York City photographed. The city isn’t exactly synonymous with the idea of the open road that features prominently in popular depictions of motorcycle riders. Yet, the book is proof that there is plenty of space to ride.

“There’s an open road in Brooklyn. There are open roads in Queens. There is an open road even in Manhattan,” Leveque said. “There are bikers of different colors and different shades that travel those open roads.”

A crucial aspect of life in the Black motorcycle community, Dingley found, is a biker’s nickname. Traditionally, a nickname is rarely chosen, it is bestowed. Leveque became “Preach” because wherever he was, he would always be talking at length about the history of Black motorcycle culture.

Even though she was there to photograph the community, eventually Dingley found that she, too, had earned a nickname.

“Mostly it was a very apt ‘Photo Lady,’” Dingley said. “It was a badge of honor for sure.”