"Mummies of the World" Opens Saturday at the Houston Museum of Natural Science

Normal people don't spend a lot of time thinking about mummies. On the rare occasions that they do, this is likely what comes to mind:

An Egyptian sarcophagus of a woman of high standing. No mummy here.

Image: Alice Levitt

For those abnormal few of us who spend a lot of time thinking about mummies, Egyptiana is often the least of our interests. There's a whole world of mummies out there. In fact, the Houston Museum of Natural Science's new exhibit, "Mummies of the World," points out early on that preserved bodies have been found on every continent.

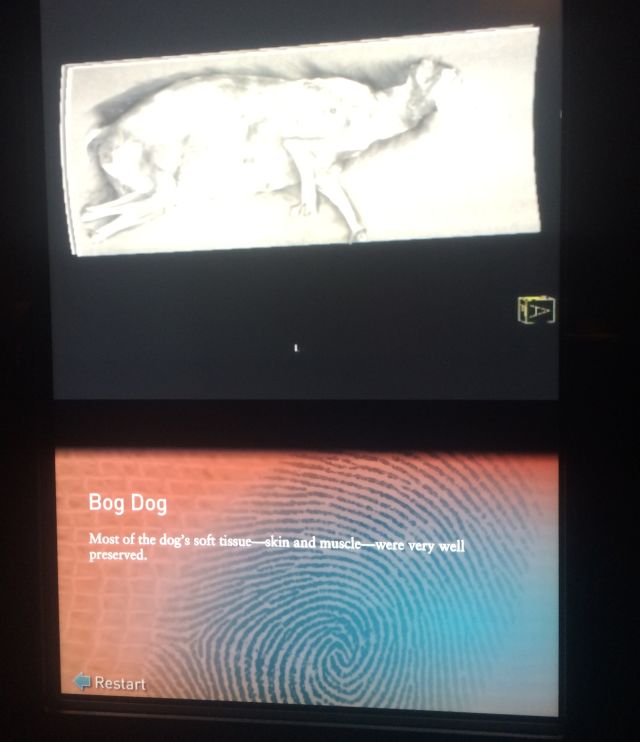

We get to know the Burlage bog dog inside and out. Mostly inside.

Image: Alice Levitt

Even Antarctica is populated with its share of frozen seal carcasses. Generally, ice-preserved animals (humans like Tyrolean iceman Ötzi and the Siberian Ice Maiden count, too) are too fragile to travel, but a mountain snow hare (circa 1950) lent to the exhibit by the same Bolzano, Italy museum that houses Ötzi is among the rare finds on display in Houston beginning this Saturday.

Those seeking discoveries from Egypt won't be disappointed. There are two Egyptians still resting in their coffins, including a priest by the name of Nes-Hor. CT scans have revealed he suffered from both arthritis and a broken left hip at the end of his life. Nearby, real-time videos of the nuclear imaging of other mummies, including a South American mother with two children and a bog-preserved dog, reveal the deepest truths about the long departed.

There is a pair of Egyptian heads, one so newly discovered it's yet to be studied. MUMAB, on the other hand, dates back only to 1994. The 76-year-old American's moniker stands for "Mummy, University of Maryland At Baltimore," where he was preserved in an experiment by Long Island University Egyptologist Bob Brier and anatomist Ronn Wade of the University of Maryland. The scientists painstakingly recreated every element of Egyptian mummification for the project, from the hooks than removed MUMAB's brain (Brier compared it at the time to strawberry yogurt) to the canopic jars in which his organs are now preserved.

Not all shrunken heads are human.

Image: Alice Levitt

Other examples of intentional, or anthropometric mummies, include a collection of shrunken heads, among the humans and monkeys made to look like humans is a sloth. They were often used as practice because they were slow and easy to catch.

Bodies from Scotland's Burns Museum Collection are early 19th century examples of the same plastination technique that Gunther von Hagens evolved last century to produce his Bodyworlds exhibits. But the flayed child and man's arm that still shows a tattoo devoted to Pope Pius V weren't intended for display—they were preserved to aid students in learning medicine without the need for the grave robbery that was common practice in an era when the general populous had no interest in donating their cadavers to an old sawbones.

Veronica Orlovits, née Skripetz, buried in Vác, Hungary.

Image: Alice Levitt

Many of the most striking specimens originated in Europe. Zweeloo Woman was unearthed in the Netherlands in 1951. Her head is missing, but what remained of her skeleton beneath her skin tanned by the acidic peat revealed exceptionally short forearms and lower legs, a bone disorder now known as Léri-Weill dyschondrosteosis. Pollen collected from her stomach showed that her final meals consisted of wheat or rye, barley and oats, as well as blackberries, whose short growing season proves she died sometime between August and October.

Michael Orlovits may have only been a miller, but he's spending eternity looking his best.

Image: Alice Levitt

Baroness Schenk von Geiern and Baron von Holz are on loan from a living relative, Dr. Manfred Freiherr von Crailsheim. At his request, the 17th century bodies are displayed as they were discovered in the family crypt in Sommersdorf Castle in the early 19th century, except for white cloths over their genitals. Traces of stockings and gloves cling to her legs and hands, but his newly hammered leather boots are in as fine fettle as his remains—researchers suspect an infectious disease killed him as no visible injuries or pathologies (save an extra vertebra) wrack his body.

Another family, the Orlovitses of Vác, Hungary, cut a more striking figure thanks to reproductions of the clothing in which they were found. Though mother Veronica was the last of the family to exit this mortal coil, she may be responsible for the demise of both her husband Michael and son Johannes, a sort of Typhoid Mary. Except the malady that affected all three was tuberculosis. It was bad news during their lives (they died in the early 19th century), but today, scientists are studying the strain of TB that killed them in order to better understand the contemporary disease. In fact, the Orlovits family could be saving modern lives.

Which makes sense, given a statement written in white on a black wall just after leaving the family's side. "There is something very unique about what you've just seen. Unlike us, mummies exist somewhere between life and death, time travelers for eternity." Thanks to HMNS, we can travel with them.

"Mummies of the World," thru May 2017. $30. Houston Museum of Natural Science, 5555 Hermann Park Dr., 713-639-4629.