Victorian England, our cultural memory tells us, was largely peopled with tragic orphans, prudish old maids, and gentlemen with stiff upper lips. We see staid figures in black-and-white photographs and conclude these were placid, dull, serious folk, enamored of discipline, self-control, and children who should be seen and not heard.

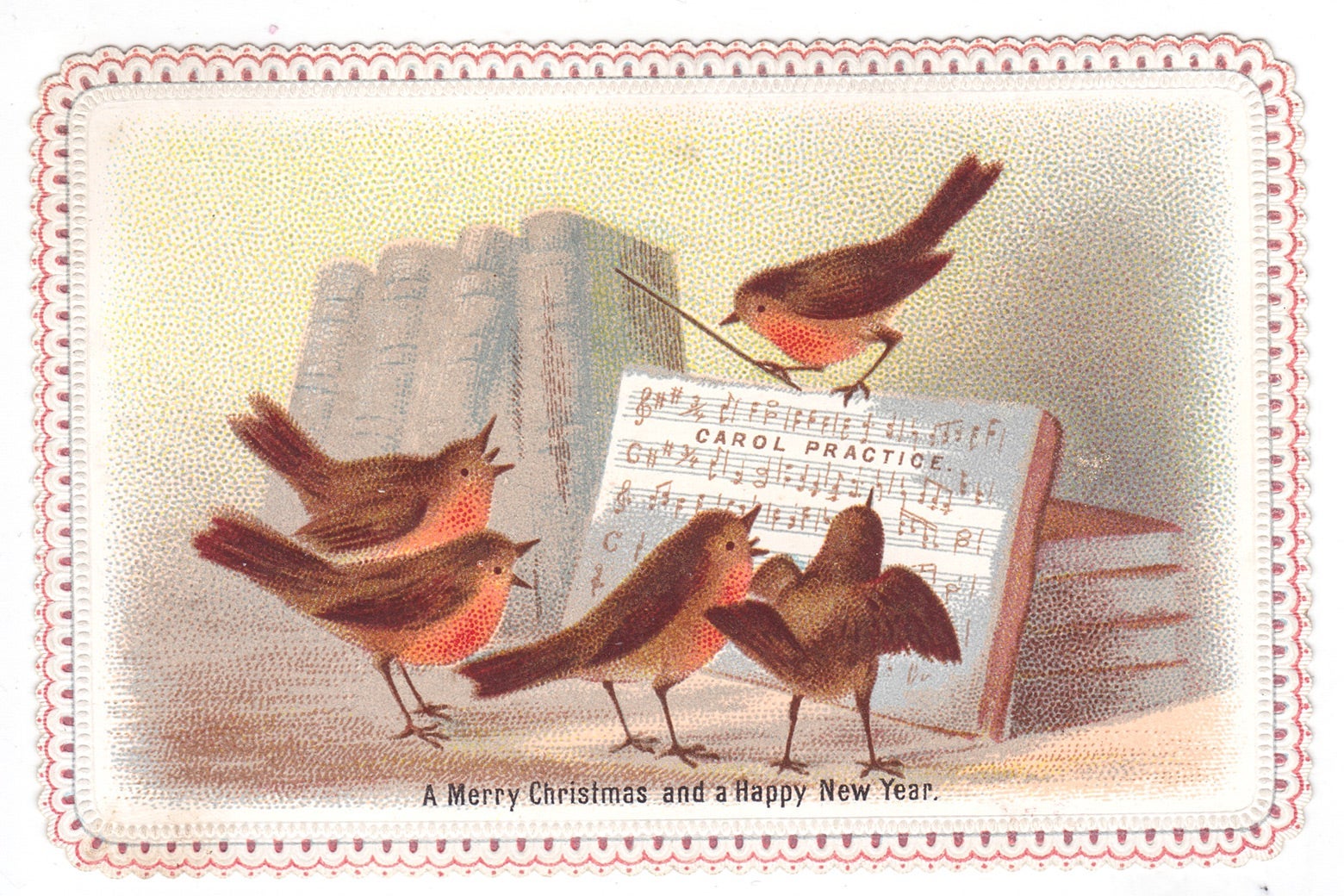

Victorian Christmas cards, however, tell a different story—one of people who relished playfulness, had an off-kilter sense of humor, and celebrated the season with exuberance rather than gravitas. Many of these originals are hilarious, but if we are willing to embrace them as more than just “weird,” images that strike a modern eye as outlandish can become a refreshing inspiration to real holiday joy.

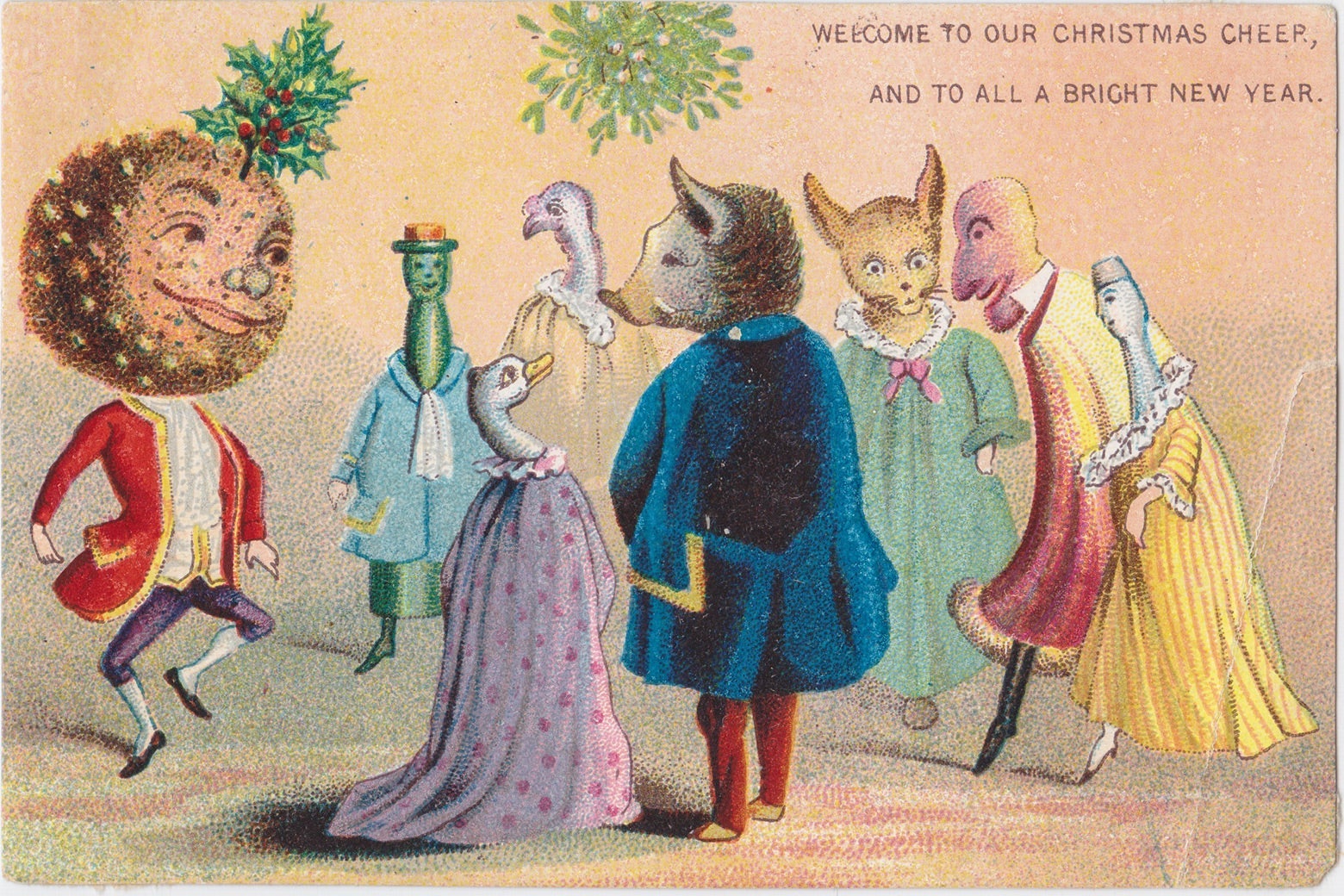

Nineteenth century cards are often charmingly self-mocking in their depiction of holiday revels. In the illustration above, the gentleman’s enthusiastic coattails defy his own skinny legs and hand gesture. He clearly hopes to tiptoe close enough to surprise his beloved into a kiss, despite the fact that a bouquet of mistletoe the size of a large shrub on his head makes him hardly inconspicuous. The fun of such visual jokes is that they may be grasped in an instant. But what made them and other bizarrely amusing productions of Victorian card-makers possible was the entire machinery of Christmas—its symbols and its hopes, its refrains and common practices, its customs of food and friends and family.

It is an exaggeration, but not a major one, to say that Christmas as we know it today began in 1843. In that year, Charles Dickens published A Christmas Carol, whose instant popularity launched a fashion for Christmas books. The beloved Queen Victoria (then 24 years old and a mother of three) was married to a dashing prince, and their family Christmas tree—a tradition Prince Albert had imported from his native Germany—inspired widespread adoption of the custom in England.

Christmas was increasingly celebrated with secular and family traditions rather than purely religious ones, and markers of the season emerged that still endure. Clement Clarke Moore’s 1823 poem, commonly known today as “ ’Twas the Night Before Christmas,” took the St. Nicholas Day (Dec. 6) tradition of stockings filled with gifts for children and relocated it to Christmas Eve. Dickens’ Scrooge and Tiny Tim taught us that the day should feature a feast of roast fowl. And the 1840 institution of the “penny post” in England—a one-penny stamp that sent a letter to any domestic address—revolutionized the mail system and paved the way for the Christmas card.

Conceived in 1843 in London by Henry Cole and illustrated by J.C. Horsley, the first Christmas card was meant to moderate Cole’s heavy holiday correspondence by providing him a respite from writing individual response letters. He had 1,000 printed. Those he did not use were offered for sale at a shilling each—the cost, then, of two large loaves of bread—a high price reflecting the fact that color had to be applied by hand to each card. They did not immediately catch on.

Chromolithography changed the game: Images were drawn in grease-based pencil on porous limestone plates, which were chemically treated and then inked so that color could be printed directly onto paper. Though this was a huge advancement, automation should not be confused with ease. The process remained extraordinarily labor-intensive. Every color required a separate plate, and a vibrant image would go through a dozen or more printings, which had to be perfectly aligned with one another to layer the necessary inks. Still, Richard March Hoe’s invention of the rotary printing press in New York in 1843 (there’s that year again!), in combination with the 1844 advent of cheap paper made from wood pulp and advancements in chromolithography processes, made mass production of color cards possible within the decade.

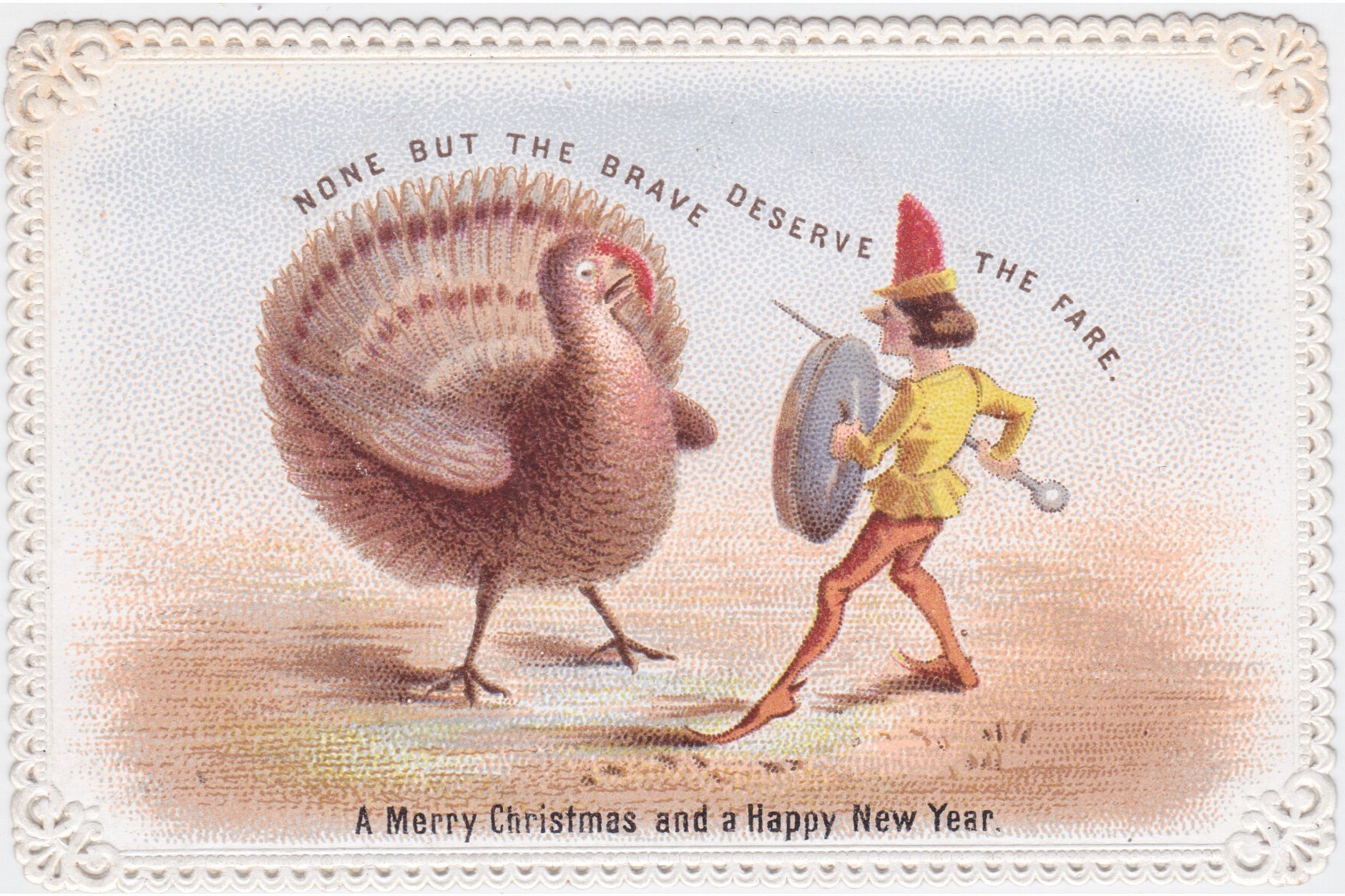

Innovations in printing and mailing enabled festive cards to circulate widely. But that does not explain why a Christmas card would feature an elf taking on a turkey with a sewing-pin sword and a salt-cellar-lid shield. And a person could be forgiven for asking: How do diminutive knights guarding fairy ladies against outraged poultry become expressions of seasonal good tidings?

For an answer, I turned to the history of Charles Goodall and Son, preeminent printers of playing cards in Britain from 1820 to 1922 and a company at the forefront of the Christmas card market in the 1850s. The Goodall family kindly provided information for this piece and shared images from its collections.

With the advent of the penny post, the company had “commenced making special writing paper with seasonable decoration and wording,” according to family historian Michael Goodall. And on their father’s death in 1851, the Goodall sons expanded the line to introduce “a range of small cards with Christmas and New Year symbols.” By 1859, the company was advertising “illuminated Christmas stationery,” which included three kinds of note paper, six card designs, and envelopes. A year later, they offered 18 kinds of cards, and in 1861, they were up to 21 designs, many produced by some of the most famous illustrators of the day. The quick increase speaks to the booming popularity of holiday cards. Goodall’s sold them for eight shillings per gross; cards that had cost the price of two loaves of bread in 1843 could now be purchased and mailed for two pence (one dinner roll) each.

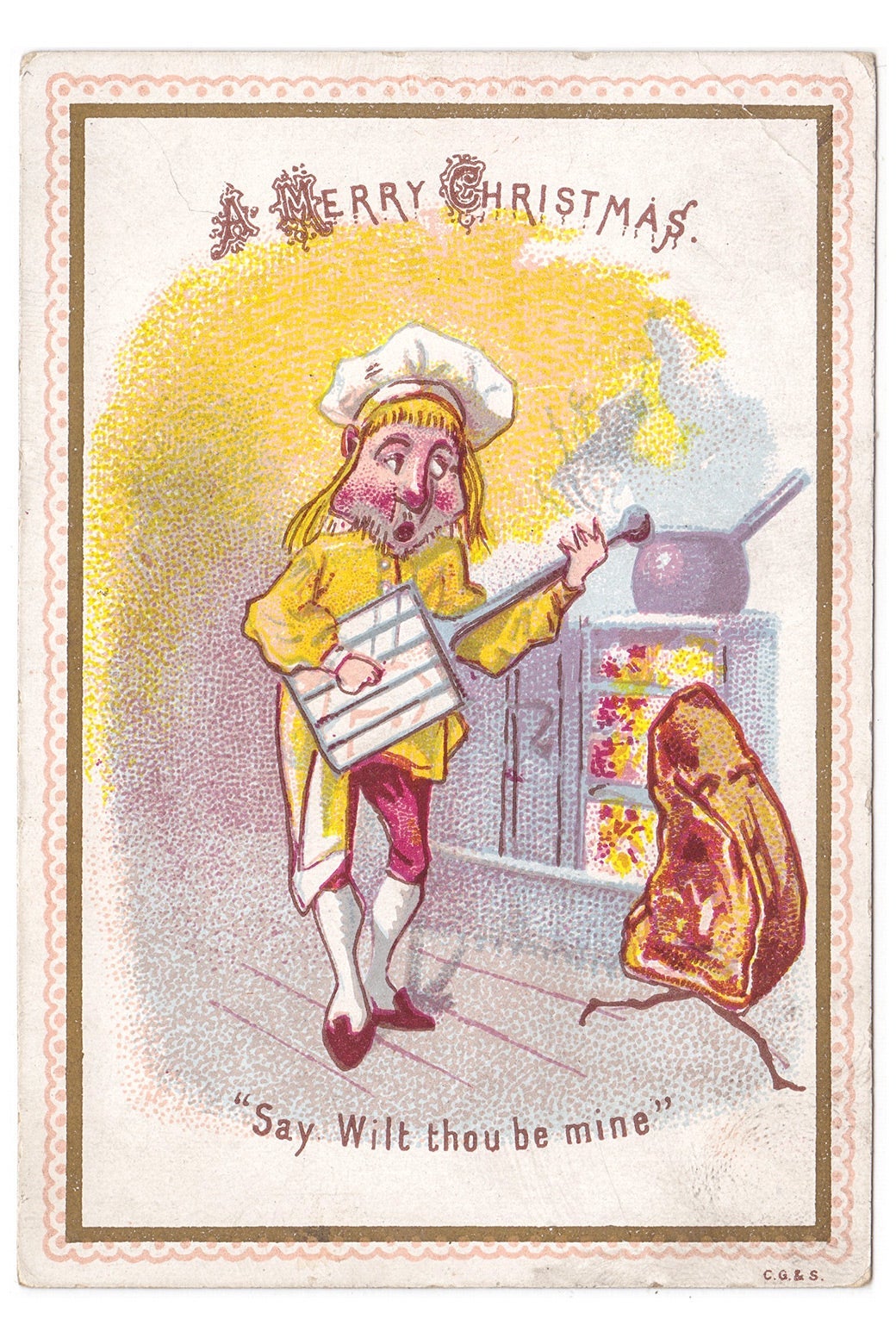

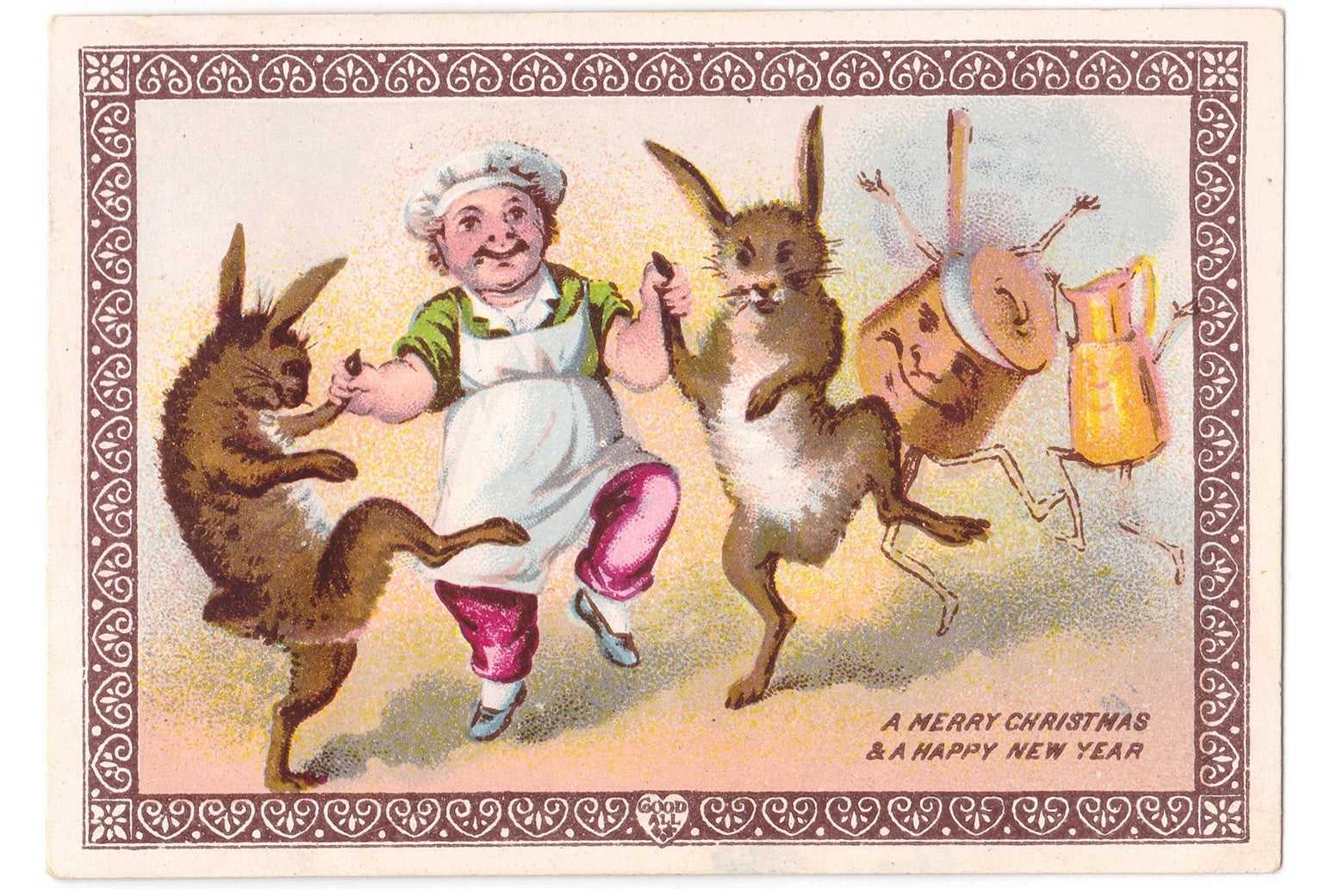

Stephen Goodall, 99, a distinguished brigadier in the British army who served in World War II, has spent the last 35 years collecting cards produced by the company his great-grandfather founded. He noted in a 2015 interview that while we might assume “religion was more important in Victorian times—and for a few years [the company] did print a few religious ones—much more so they did humorous ones.” The humor turned on taking elements associated with Christmas—the roast fowl, the family merriment—and depicting them with a zany twist, often including a dose of fairyland magic and a relish of witticisms. Cavorting animals feature liberally, along with puns, fairy pranks, pratfalls, and shenanigans. Winter is slippery, we are reminded. Animals with stunned, humanized expressions are hilarious, and cherubic children are just the right size to fly away on the back of a plump goose.

Food themes dominate, with one recurring joke being the threat of an escaping Christmas dinner. Much like the infamous runaway gingerbread man (a story originally published in 1875 in St. Nicholas Magazine), dinner ingredients sprout working legs and dash off. One wants to pity the mournful cook trying to woo a fleeing cut of beef back to the kitchen by singing “Wilt thou be mine” and strumming on a lute that is actually a long-handled grill pan, but it’s hard not to laugh at his long face. Merrier versions depict unsuspecting dinner ingredients frolicking gleefully with the cook.

Numerous images turn a round, freckled ball into a head, anthropomorphizing what English viewers even today would recognize as a traditional Christmas pudding. A dense sort of cake studded with raisins, figs, or other dried fruits (think of “so bring us some figgy pudding”), it is first tied up in a cloth and steamed, then decorated with a sprig of holly, doused with rum or brandy, and brought flaming to the table where—once the festive flames burn out—it is eaten with caramel, brandy butter, or custard sauce. Why not usher in Christmas cheer for your friends with a bevy of animals and liquor bottles dressed in holiday finery, following the lead of a jovial Christmas pudding in what is surely about to be some dancing?

Other cards play in a more madcap way on the notion of Christmas bounty. In one scene reminiscent of 1865’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, we find creatures and foodstuffs organizing themselves to dance a quadrille. You’d think the plucked turkey would be embarrassed at its own nakedness, but the introductory bows of everyone else draw humorous attention to the fact that the turkey is partnered with a Champagne bottle who, unfortunately for the dancing, has no legs.

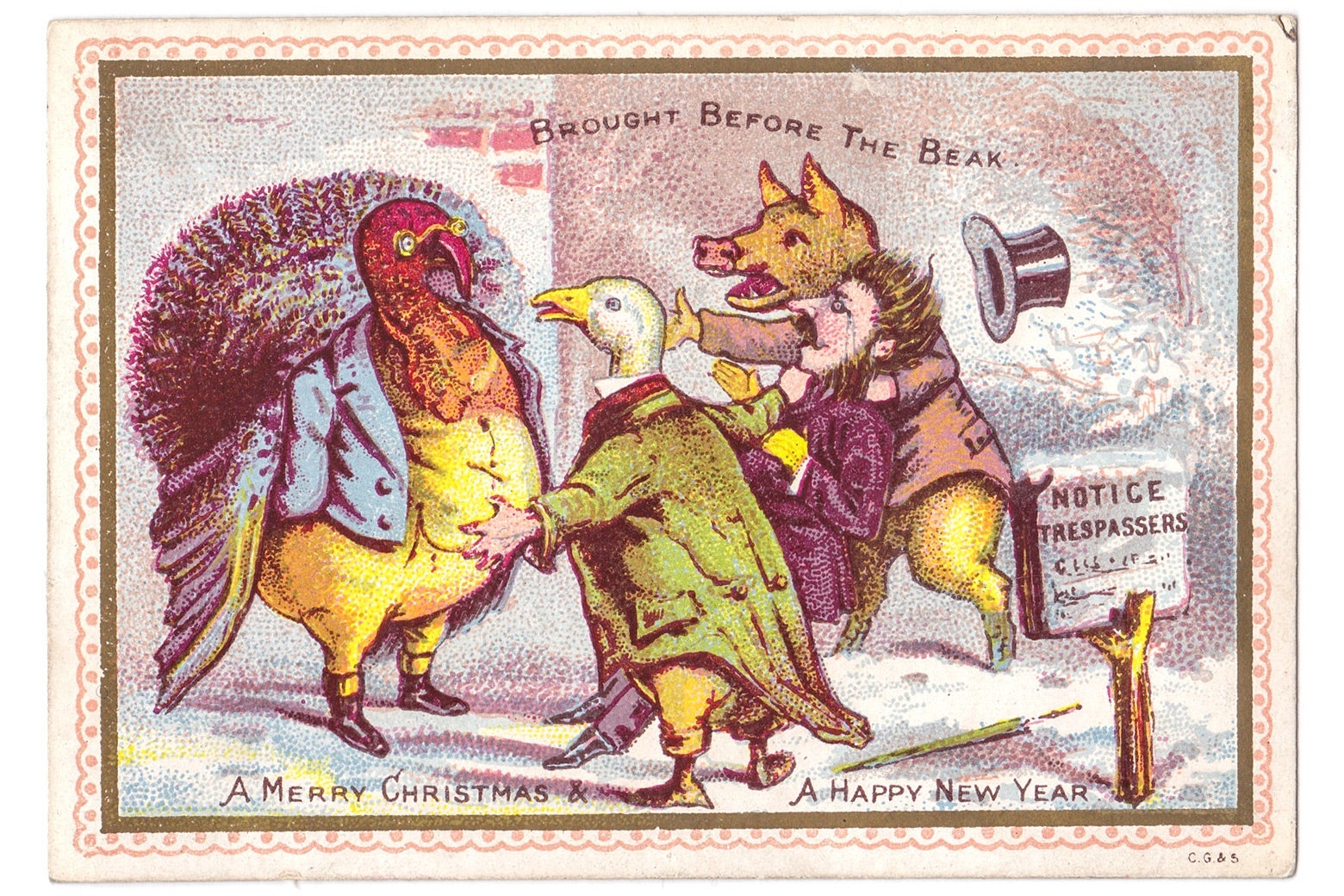

Once one has ventured down the path of dancing dinners, it’s only a short hop to oddball puns. “Brought before the beak,” this card jests, “beak” being Victorian slang for magistrate, while the “trespasser” forced to face the portly turkey is the only human in this animal world.

Maddy Goodall, heritage coordinator for Humanists UK, is grateful her grandfather Stephen preserved the ephemera—cards, diaries, letters, and photos—that “offer glimpses into who [her family] were.” She writes in an email: “There’s always been a thread of slightly strange humour in the family, even as certain generations in particular have clearly had a lot of reserve. … It seems somehow both so fitting, and so surprising, that they did have this tendency towards the bizarre and the lighthearted.”

It’s possible that the particularly quirky sense of humor of a single family filtered through the generations and into holiday cards produced by the gross for an eager public. It is even more appealing to imagine that their combination of reserve and lightheartedness was characteristic of their time—that one legacy the 19th century bestows upon us is the recognition that a person is not diminished in dignity by choosing delight periodically.

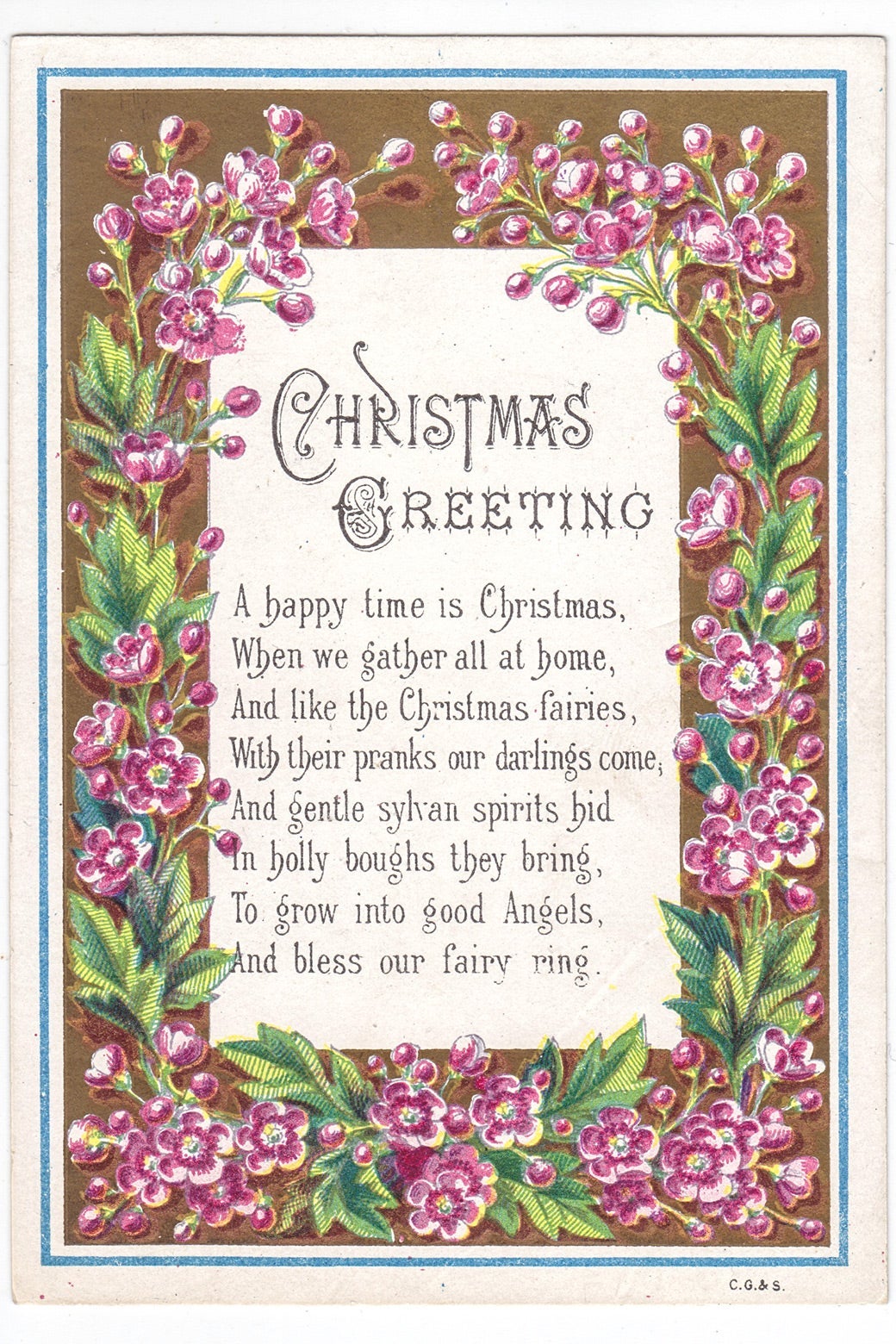

This lovely card illuminates, probably unwittingly, the curious hijinks in the others. Its poem defines Christmas as a time for joyful gathering, while reminding readers that modern celebrations were fashioned out of pagan roots. And its garland of hellebore, or Lenten rose, perfectly encapsulates this hybrid: In the Victorian language of flowers, this winter bloom carried associations with both ancient magic and the promise of hope for the future. As the traditions of modern Christmas were coalescing, stockings, decorated trees, and mass-produced cards, which seem so familiar to us now, were more experimental than the trappings of older winter solstice celebrations, such as puddings, witty pranks, and fairy stories. Small wonder, then, that these early cards sought to mix the mischief of sylvan spirits with newer symbols of the season, in trying to work out the formula for Christmas magic.

The cards that do so most successfully are, like the following, a beautiful amalgam of all the good things: Cherubs parading with holly and mistletoe and libations, beneath an ornate poem wishing everyone “plenty of mince pies, and puddings of gigantic size,” offer a lesson in cramming much deliciousness of every sort into even a small space.

What if we took a page from the Victorian scrapbook and embraced the holidays as a time for the respite offered by gentle pranks and whimsical nonsense? Aunt Felicity Goodall observed over the phone, before running off to adjudicate a game of patience in which, apparently, some family members were cheating, “You know that saying ‘The past is another country’? Well, I think the past is just as weird as we are. Just as quirky.”

It feels good to remember that the weird and the wonderful can be sources of sustenance. Reaching back through these charming bits of paper and ink, we can form what Maddy Goodall describes as a “beautiful, tangible connection to people who otherwise seem so far removed.” And we can appreciate how cards of our own might forge similar connections to loved ones who may be, again this year, far away, but with whom we share moments of boundless joy.