Chapter 6: Early Christian and Byzantine Art

The beginnings of identifiable Christian art can be traced to the end of the second century and the beginning of the third century. Considering the Old Testament prohibitions against graven images, it is important to consider why Christian art developed in the first place. The use of images will be a continuing issue in the history of Christianity. The best explanation for the emergence of Christian art in the early Church is due to the important role images played in Greco-Roman culture. As Christianity gained converts, these new Christians had been brought up on the value of images in their previous cultural experience and they wanted to continue this in their Christian experience. Nevertheless, in an effort to firmly establish their newfound Christian identity and to use art as a means to commune with the Divine, art took on an entirely distinct role and style.

Let's explore this period in a little more detail.

Early Christian Art

The term Early Christian Art refers to the earliest art depicting Christian subject matter, which dates to the end of the second century CE. Many examples come from Rome, which served as a center of early Christianity, and exhibit the influence of Roman art. The earliest representations of Christ were not meant to be perceived as literal portraits, rather they were depictions of the Good Shepherd as a symbol of Christ, typically portrayed as a young, beardless man with a lamb across his shoulders. By about the 5th century CE, depictions of Christ evolve to resemble the more recognizable bearded figure, often depicted with a halo and wearing the robes of a Roman emperor.

Byzantine Art

The formation of the Byzantine Empire dates back to a division that occurred after the death of the emperor Theodosius in 395 CE. when his two sons split the empire, creating what comes to be known as the Eastern and Western Roman Empires. The Western Roman Empire collapses in 476 CE, but the Eastern Empire, which comes to be known as the Byzantine Empire, continues until 1453, when it is captured by the Ottoman Empire. As it was formed from the Eastern Roman Empire, Byzantine art and architecture strongly resemble Roman art and architecture. Historians generally pinpoint the development of a distinct Byzantine style to the reign of the Emperor Justinian in the 6th century CE. Byzantine art is characterized by,

- An elongation of the human figure and a flattened, two-dimensional feel.

- The extensive use of gold in religious art and architecture, which was used to symbolize sanctity.

- Use of rich colors and imagery.

Byzantine Art

To speak of “Byzantine Art” is a bit problematic, since the Byzantine Empire and its art spanned more than a millennium and penetrated geographic regions far from its capital in Constantinople. Thus, Byzantine art includes work created from the fourth century to the fifteenth century and encompassing parts of the Italian peninsula, the eastern edge of the Slavic world, the Middle East, and North Africa.

Emperor Constantine adopted Christianity and in 330 CE moved his capital from Rome to Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul), at the eastern frontier of the Roman Empire. Christianity flourished and gradually supplanted the Greco-Roman gods that had once defined Roman religion and culture. This religious shift dramatically affected the art that was created across the empire.

The earliest Christian churches were built during this period, including the famed Hagia Sophia, which was built in the sixth century under Emperor Justinian. Decorations for the interior of churches, including icons and mosaics, were also made during this period. Icons, such as the Virgin (Theotokos) and Child between Saints Theodore and George, served as tools for the faithful to access the spiritual world—they served as spiritual gateways.

Similarly, mosaics, such as those within the Church of San Vitale in Ravenna, sought to evoke the heavenly realm. In this work, ethereal figures seem to float against a gold background that is representative of no identifiable earthly space. By placing these figures in a spiritual world, the mosaics gave worshipers some access to that world as well. At the same time, there are real-world political messages affirming the power of the rulers in these mosaics. In this sense, the art of the Byzantine Empire continued some of the traditions of Roman art.

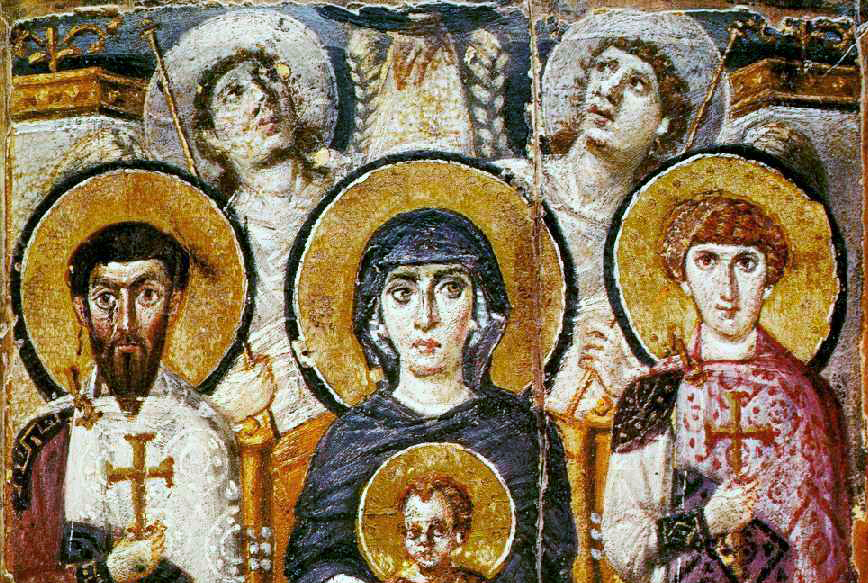

Virgin (Theotokos) and Child between Saints Theodore and George

One of thousands of important Byzantine images, books, and documents preserved at St. Catherine’s Monastery, Mount Sinai (Egypt) is the remarkable encaustic icon painting of the Virgin (Theotokos) and Child between Saints Theodore and George (“Icon” is Greek for “image” or “painting” and encaustic is a painting technique that uses wax as a medium to carry the color).

The icon shows the Virgin and Child flanked by two soldier saints, St. Theodore to the left and St. George to the right. Above these are two angels who gaze upward to the hand of God, from which light emanates, falling on the Virgin.

Tier 1: Content--Virgin (Theotokos) and Child between Saints Theodore and George

Like all artwork, the content of this work contains elements worth exploring. As you consider this work, refer to the elements of art listed in Tier 1: Content.

While there are many significant features of this work, pictorial space, composition, and scale are prominent and informative. The painter selectively used the classicizing style inherited from Rome. The faces are modeled; we see the same convincing modeling in the heads of the angels (note the muscles of the necks) and the ease with which the heads turn almost three-quarters. The space appears compressed, almost flat, at our first encounter. Yet we find spatial recession, first in the throne of the Virgin, where we glimpse part of the right side and a shadow cast by the throne; we also see a receding armrest as well as a projecting footrest. The Virgin, with a slight twist of her body, sits comfortably on the throne, leaning her body left, toward the edge of the throne. The child sits on her ample lap as the mother supports him with both hands. We see the left knee of the Virgin beneath convincing drapery, with folds that fall between her legs.

At the top of the painting, an architectural member turns and recedes at the heads of the angels. The architecture helps to create and close off the space around the holy scene. The composition displays a spatial ambiguity that places the scene in a world that operates differently from our world. The ambiguity allows the scene to partake of the viewer’s world but also separates the scene from the normal world.

New in our icon is a use of scale that we might call a “hierarchy of bodies.” Theodore and George stand erect, feet on the ground, and gaze directly at the viewer with large, passive eyes. While looking at us, they show no recognition of the viewer and appear ready to receive something from us. The saints are slightly animated by the lifting of a heel by each, as though they slowly step toward us.

The Virgin averts her gaze and does not make eye contact with the viewer. The ethereal angels concentrate on the hand above. The light tones of the angels and especially the slightly transparent rendering of their halos give the two an otherworldly appearance.

We can describe the differing appearances as saints who seem to inhabit a world close to our own (they alone have a ground line), the Virgin and Child who are elevated and look beyond us, and the angels who reside near the hand of God transcend our space. As the eye moves upward, we pass through zones: the saints, standing on the ground and therefore closest to us, and then upward and more ethereal until we reach the holiest zone, that of the hand of God. These zones of holiness suggest a cosmos of the world, earth, and real people through the Virgin, heavenly angels, and finally the hand of God. The viewer who stands before the scene makes this cosmos complete, from “our earth” to heaven.

San Vitale and the Justinian Mosaic

San Vitale is one of the most important surviving examples of Eastern Roman “Byzantine” Empire architecture and mosaic work. It was begun in 526 or 527 under Ostrogothic rule. It was consecrated in 547 and completed soon after.

One of the most famous images of political authority from the Middle Ages is the mosaic of Emperor Justinian and his court in the sanctuary of the church of San Vitale in Ravenna, Italy. This image is an integral part of a much larger mosaic program in the chancel (the space around the altar). A major theme of this mosaic program is the authority of the emperor in the Christian plan of history.

The mosaic program can also be seen as giving visual testament to the two major ambitions of Justinian’s reign: as heir to the tradition of Roman Emperors, Justinian sought to restore the territorial boundaries of the Empire. As the Christian Emperor, he saw himself as the defender of the faith. As such, it was his duty to establish religious uniformity or Orthodoxy throughout the Empire.

In the chancel mosaic, Justinian is posed frontally in the center. He is haloed and wears a crown and a purple imperial robe. He is flanked by members of the clergy on his left, with the most prominent figure, the Bishop Maximianus of Ravenna, labeled with an inscription. To Justinian’s right appear members of the imperial administration, identified by the purple stripe, and at the very far left side of the mosaic appears a group of soldiers. This mosaic thus establishes the central position of the Emperor between the power of the Church and the power of the imperial administration and military. Like the Roman emperors of the past, Justinian has religious, administrative, and military authority.

The clergy and Justinian carry in sequence (from right to left) a censer, the gospel book, the cross, and the bowl for the bread of the Eucharist. This identifies the mosaic as the so-called "Little Entrance," which marks the beginning of the Byzantine liturgy of the Eucharist. Justinian’s gesture of carrying the bowl with the bread of the Eucharist can be seen as an act of homage to the True King, who appears in the adjacent apse mosaic.

Questions to Consider

- How does this work transmit the authority of Justinian as a ruler?

- In what ways does this work communicate a connection of the divine to the viewer?

A closer examination of the Justinian mosaic reveals an ambiguity in the positioning of the figures of Justinian and the Bishop Maximianus. Overlapping suggests that Justinian is the closest figure to the viewer, but when the positioning of the figures on the picture plane is considered, it is evident that Maximianus’s feet are lower on the picture plane, which suggests that he is closer to the viewer. This can perhaps be seen as an indication of the tension between the authority of the Emperor and the Church.

This content is provided to you freely by BYU Open Learning Network.

Access it online or download it at https://open.byu.edu/history_of_the_fine_arts_music/byzantine_art.