Abstract

Aims/hypothesis

Limited data exist on the association between maternal diet quality during pregnancy and metabolic traits in offspring during early childhood, which is a sensitive period for risk of obesity-related disorders later in life. We aimed to examine the association of maternal diet quality, as indicated by the Healthy Eating Index-2010 (HEI), in pregnancy with offspring metabolic biomarkers and body composition at age 4–7 years.

Methods

We used data from 761 mother–offspring pairs from the Healthy Start study to examine sex-specific associations of HEI >57 vs ≤57 with offspring fasting glucose, leptin, cholesterol, HDL, LDL, percentage fat mass, BMI z score and log-transformed insulin, 1/insulin, HOMA-IR, adiponectin, triacylglycerols, triacylglycerols:HDL, fat mass, and sum of skinfolds. Multivariable linear regression models accounted for maternal race/ethnicity, age, education, smoking habits during pregnancy and physical activity, and child’s age.

Results

During pregnancy, mean (SD) HEI score was 55.0 (13.3), and 43.0% had an HEI score >57. Among boys, there was an inverse association of maternal HEI with offspring glucose, insulin, HOMA-IR and adiponectin. For instance, maternal HEI >57 was associated with lower fasting glucose (−0.11; 95% CI −0.20, −0.02 mmol/l), and lower concentrations of: insulin by 15.3% (95% CI −24.6, −5.0), HOMA-IR by 16.3% (95% CI −25.7, −5.6) and adiponectin by 9.3% (95% CI −16.1, −2.0). Among girls, there was an inverse association of maternal HEI with insulin and a positive association with LDL. However, following covariate adjustment, all estimates among girls were attenuated to the null.

Conclusions/interpretation

Greater compliance with the USA Dietary Guidelines via the HEI may improve the maternal–fetal milieu and decrease susceptibility for poor metabolic health among offspring, particularly boys. Future studies are warranted to confirm these associations and determine the underlying mechanisms.

Graphical abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Maternal nutritional status during pregnancy is a key contributor to the intrauterine environment and fetal development. Both historical and contemporary studies have exemplified the importance of macronutrient intake and balance, as well as intake of specific nutrients (e.g., folate, calcium, iron), for a range of offspring health outcomes, including obesity and related sequelae [1]. However, assessment of individual nutrients fails to capture the overall quality of diet and the interplay between nutrients and non-nutrient components in foods [2]. Of increasing interest are diet indices, such as the Healthy Eating Index-2010 (HEI), that measure dietary patterns marked by higher consumption of vegetables, fruit, fish and unsaturated fats, in conjunction with lower intakes of red and processed meat and saturated fats [3,4,5].

Few studies have assessed the HEI among pregnant women, and most have focused on associations with offspring body composition [6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. Biomarkers of metabolic risk, particularly alterations in insulin resistance and secretion, are also important to consider as differences in such biomarkers have been found in children and adults within normal ranges of weight [14, 15]. Sex differences in body composition, glucose homeostasis, insulin signalling and lipid metabolism typically diverge during adolescence [16, 17], but have been detectable as early as at birth [18, 19], and may be attributable to differences in fetal response to the gestational environment [19,20,21]. Further, studies of murine and human placentas have shown clear sex-specific differences in gene expression with respect to maternal diet during pregnancy [22,23,24].

The current study assessed whether diet quality during pregnancy influences offspring metabolic health. We calculated the HEI [25], based on the 2010 USA Dietary Guidelines, and examined associations with biomarkers of glucose homeostasis, the adipoinsular axis, lipid metabolism and measures of body composition among offspring in early childhood (4–7 years of age), a sensitive life stage for development of obesity and risk of chronic disease [26, 27]. Given documented sex differences in the outcomes of interest (body composition and metabolic biomarkers) in youth [17], and evidence that fetal response to the in utero environment differs for male vs female fetuses [24], we hypothesised that a higher-quality diet during pregnancy is associated with lower adiposity and biomarkers of metabolic risk, and that these associations differ by offspring sex.

Methods

Study participants and design

The Healthy Start study is a multi-ethnic pre-birth cohort of mother–offspring pairs who were enrolled at <24 weeks from prenatal clinics at the University of Colorado Hospital between 2009 and 2014. Women were excluded if they had prior diabetes, a history of prior premature birth with a gestational age (GA) <25 weeks or fetal death, asthma with active steroid management, serious psychiatric illness or multiple gestations. During pregnancy, women completed questionnaires on demographic characteristics, personal and family medical histories, and behaviours during pregnancy. Offspring returned for an in-person visit when they were between 4 and 7 years of age, during which body composition, anthropometry and a fasting blood sample were obtained. All women provided written informed consent and children 7 years of age or older provided assent. The study protocol and procedures were approved by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board. The Healthy Start study is registered as an observational study at ClinicalTrials.gov (registration no. NCT02273297).

Mother–offspring pairs were eligible for the current analysis if women had at least one dietary recall during pregnancy (N = 1366), and had an offspring who attended an in-person child visit at age 4–7 years (N = 907). We excluded offspring without air displacement plethysmography or blood assay data (N = 134), and women missing components necessary to calculate the HEI (N = 12). The final sample included 761 mother–offspring pairs (Fig. 1). Participants who were included were similar to those excluded, except those included had a slightly older maternal age (~1 year) and a greater percentage reported a household income ≤$70,000 (36.7% vs 27.9%).

Maternal dietary intake and the HEI

Beginning in the first trimester (GA <13 weeks), maternal diet was assessed via the Automated Self-Administered 24 h Dietary Recall (ASA24) [28]. Details on the frequency of ASA24 completion by GA and offspring sex can be found in electronic supplementary material (ESM) Table 1. The mean number of ASA24s per woman was between three and five. A National Cancer Institute SAS macro (https://epi.grants.cancer.gov/hei/developing.html; accessed June 2021) was used to generate the HEI total scores from averaged recalls for each participant, which has been extensively reviewed [4]. Briefly, the model estimates the distribution of usual HEI scores based on a multivariate distribution (covariates: pre-pregnancy BMI, gravidity and smoking status) of usual intakes, which allows for the assessment of diet quality over time [4]. The HEI is a measure of diet quality used to assess compliance with USA Dietary Guidelines that are intended to be met over time and not necessarily every day [4, 29]. The HEI has 12 components assessed on a density basis, e.g. per 4184 kJ (1000 kcal) or as a percentage of kilojoules. Alcohol was not included in the HEI because all participants consumed under 13 g of alcohol per 4184 kJ for each recall, which is below the threshold for inclusion of calories from alcohol.

Offspring body composition and metabolic biomarkers

Fat mass (FM) and fat-free mass (FFM) were measured using whole body air displacement plethysmography (BodPod, Life Measurement, USA) with the Pediatric Option [30]. Offspring weight was measured using an electronic scale. Triceps, subscapular and mid-thigh skin-fold thicknesses were measured using Lange Skin-fold Calipers (Beta Technology, USA) to the nearest 1.0 mm by trained nurses. Body composition measurements for each participant were taken in triplicate and the mean of the two closest measures was used for analyses. Skinfolds were summed (sum of skinfolds) as a measure of subcutaneous adiposity. Age-specific BMI z scores were calculated according to the World Health Organization growth reference [31, 32].

Fasting triacylglycerols (TAGs), total cholesterol, HDL, LDL and glucose were measured using manufacturer-prepackaged enzymatic kits and the AU400e Chemistry Analyzer (Olympus America, USA). Insulin was measured using a radioimmune assay, and leptin and adiponectin were measured using a Multiplex assay kit, all by Millipore (USA). We calculated the ratio of TAGs:HDL as an indicator of an atherogenic lipid profile and a strong correlate of insulin resistance [33, 34], 1/(fasting insulin) as a measure of insulin sensitivity [35] and an updated HOMA-IR [36]. The inter-assay CVs of these biomarkers were all <6.0%.

Covariate assessment

Maternal race/ethnicity, educational attainment, parity and smoking status during pregnancy were self-reported via questionnaire. Physical activity level was assessed twice during pregnancy with the Pregnancy Physical Activity Questionnaire as metabolic equivalent tasks (METs) in hours/week and averaged as a global measure of physical activity during pregnancy [37]. We calculated maternal pre-pregnancy BMI (kg/m2) based on pre-pregnancy weight obtained from medical records among women who received primary care from an affiliated University of Colorado doctor (89%) or from self-report (11%), and height measured at the first research visit. Early childhood dietary data were collected via two ASA24 dietary recalls (one weekend and one weekday), with parents as a proxy, and nutrient and caloric intakes were derived using the Nutrition Data System for Research software package. We derived the child HEI scores using the same procedure as for the mothers, except the 2015 USA Dietary Guidelines were used to align with the timing of data collection. Offspring physical activity was measured using wGT3X-BT ActiGraph accelerometers (Pensacola, FL, USA) [38] and categorised based on youth-specific cut-points [39]. Details on sample sizes for covariates are reported in ESM Tables 2, 3.

Statistical analysis

Prior to the main analysis, we examined bivariate associations of perinatal characteristics chosen based on prior knowledge with HEI. To create the most parsimonious model, we used bivariate analysis to select only those characteristics associated with HEI and offspring metabolic and body composition outcomes. To better understand differences in metabolic markers by offspring sex, we compared the mean differences in biomarkers and adiposity indicators in early childhood between boys and girls. The p values for an interaction by sex were not statistically significant for some of the outcomes (e.g., insulin, leptin, HDL) when tested in an unadjusted or covariate-adjusted model (Model 2, see below) that included HEI and sex as main and interaction terms. However, we observed substantially different results between the sexes, which, in conjunction with our a priori research interest, informed our decision to present all results stratified by sex.

For the primary analysis, we took the mean of food group servings across multiple recalls in pregnancy for each participant in light of prior evidence indicating that maternal diet quality is consistent across pregnancy [40, 41], and because the HEI includes food components that are consumed both episodically and regularly. In a previous study within this cohort, a score of >57, representing the upper two quintiles of the HEI distribution, was associated with neonatal adiposity [42]. Given the similarity of this threshold to HEI >58, which represented the upper two quintiles among participants in the present study, and to HEI ≥59, which corresponds with mean diet quality for Americans [43], we dichotomised the score as >57 vs ≤57 given its biological relevance among Healthy Start mother–child dyads and to facilitate comparability across studies in this cohort [42].

We used linear regression models to estimate the association of maternal HEI score >57 vs ≤57 with offspring glucose concentration, insulin, 1/insulin, HOMA-IR, adiponectin, leptin, cholesterol, TAGs, HDL, LDL, TAGs:HDL ratio, percentage fat mass (%FM), FM, BMI z score, and sum of skinfolds. Offspring insulin concentration, 1/insulin, HOMA-IR, adiponectin, TAGs and TAGs:HDL ratio, and measures of FM, and sum of skinfolds, were natural log transformed due to non-normal distributions. We present the results within the text as per cent change, calculated as: %change = (exp(β) − 1) × 100.

Multivariable models were specified as follows. Model 1 adjusted for mean GA at ASA24 to account for differences in GA at dietary recalls. Model 2 included mean GA at ASA24, and confounders to the relationship between maternal diet and offspring health (maternal race/ethnicity, age, education, pre-pregnancy BMI and prenatal smoking habits, and child’s age at outcome assessment). Model 3: potential mediators such as maternal physical activity in pregnancy, gestational weight gain status and offspring birthweight. Model 4: all covariates in Model 2 plus child HEI score and physical activity levels, which may be related to maternal diet during pregnancy through backdoor paths. In our interpretation of results, we focus on estimates from Model 2, and assess for consistency in the direction, magnitude and precision of estimates across models to ensure robustness of associations. Sample sizes of covariates are reported in ESM Tables 2, 3.

To enhance interpretation of findings and to understand the interrelatedness of metabolic biomarkers and adiposity indicators in early childhood, we calculated Spearman correlations among markers of body measures and metabolic biomarkers in offspring.

Assessment of residuals from multivariable models indicated a normal distribution. Given the collinearity of outcomes in this study, testing for multiple comparisons was likely overly conservative [44]. However, to account for potential false findings, we tested mean differences in levels of biomarkers (log transformed as appropriate) by maternal HEI >57 vs ≤57 and adjusted p values using the bootstrap method, with 20,000 resamples performed with replacement within each sex [45, 46].

Sensitivity analyses

First, to check for differences in HEI during early (<27 gestational weeks) vs late pregnancy (≥27 gestational weeks), we compared mean scores among women who had data at both time-points (N = 424) and calculated Pearson correlations. In this subsample of 220 boys and 204 girls, we assessed the association between HEI and offspring outcomes during early and late pregnancy. In addition, to allow for potential changes in diet quality across pregnancy, we assessed associations of having an HEI score >57 in both early and late pregnancy (vs not) with offspring outcomes. Second, although the HEI is based on ratios of nutrient intake per total energy, we adjusted models for total energy intake kilocalories to ensure our findings were not solely driven by energy intake. Third, to assess for a dose–response relationship between HEI and offspring metabolic and body composition outcomes we modelled HEI as a continuous variable, as well as in quintiles, and tested for a linear trend by fitting the median HEI score of each quintile as a continuous variable. Fourth, to ensure that our findings were independent of the diet change that often accompanies a diagnosis of gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM), we excluded these women (N = 17 among boys, N = 18 among girls).

Finally, although some studies suggest that HEI >80 represents a high-quality diet [47], there is no validated HEI threshold in pregnant women. Only a small proportion of women in our sample had an HEI >80 (2.10%), and therefore we were underpowered to perform stratified analyses using this cut-off.

Results

The mean (SD) GA in weeks at time of recall for women who completed only one dietary assessment was 19.6 (4.8) (data not shown). For women who completed more than one dietary recall (N = 636), 97% completed ASA24s in the second (GA 13–26 weeks) and third trimesters (GA 27 weeks to delivery). On average, women had an HEI score of 55.0 (SD 13.3) throughout pregnancy, and 43.0% had a score >57, a threshold associated with lower adiposity at birth in this cohort. On average, women with a score >57 consumed fewer carbohydrates, less total fat and slightly less protein compared with women with a score ≤57 (257.9 g [SD 51.1] vs 262 g [SD 56.1] of carbohydrates, 76.9 g [SD 13.8] vs 82.2 g [SD 15.57] of total fat and 82.7 g [SD 12.9] vs 81.8 g [SD 13.0] of protein).

Table 1 shows the sample sizes, mean age, distribution of child race/ethnicity, biomarkers and adiposity indicators between boys and girls at 4–7 years. The mean age at body composition measurement and blood draw was 4.8 (SD 0.69) in boys and 4.8 (SD 0.71) in girls. There were no racial/ethnic differences in the distribution of boys and girls. Boys had slightly higher levels of glucose mmol/l (4.62 [SD 0.37] vs 4.52 [SD 0.33]; p value <0.001) and as expected were larger overall. Among girls, we observed higher leptin and TAG concentrations and a slightly greater sum of skinfolds.

At delivery, the women were 28.3 (SD 6.1) years of age. A higher HEI score was associated with higher education, lower pre-pregnancy BMI, not smoking during pregnancy and lower physical activity (Table 2). Within each offspring sex there were similar patterns of associations when assessing maternal characteristics and HEI score during pregnancy. The HEI score was slightly higher among women of male vs female offspring (55.9 [SD 13.3] vs 54.1 [SD 13.3]; p = 0.07), although there were no differences in the proportion of women with HEI >57 by sex (p = 0.37). Associations of maternal characteristics with offspring outcomes generally tracked within each sex (ESM Tables 2, 3). For instance, offspring of Hispanic women and women with lower educational status or higher pre-pregnancy BMI had higher concentrations of glucose and HOMA-IR.

Among boys, there was an inverse association of maternal HEI with offspring glucose (−0.11; 95% CI −0.20, −0.02), insulin (%change −15.3; 95% CI −24.6, −5.0), HOMA-IR (%change −16.3; 95% CI −25.7, −5.6), adiponectin (%change −9.3; 95% CI −16.1, −2.0) and TAGs:HDL (%change −0.3; 95% CI −0.6, 0.01) in unadjusted models (Table 3); however, the upper CI for the estimate of TAGs:HDL crossed the null. These associations were materially unchanged after adjusting for confounders or potential mediators, though estimates for glucose became only marginally significant. Following further adjustment for the child’s HEI score and physical activity levels, the magnitudes of associations for glucose, adiponectin and TAGs:HDL were slightly attenuated and no longer reached the threshold of statistical significance.

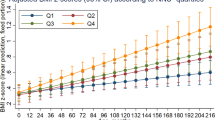

When modelling HEI as quintiles or as a continuous variable, we observed similar findings to HEI >57, with a significant linear trend indicating a dose–response relationship between higher-quality diet and lower glucose, insulin and adiponectin levels among boys (ESM Table 4). Associations of HEI as quintiles and continuous variables among girls are reported in ESM Table 5. After adjusting p values for multiple comparisons, we did not observe substantial differences in our findings for the insulin-based metrics (insulin, 1/insulin and HOMA-IR bootstrap p values <0.05) (ESM Fig. 1).

Among girls (Table 4), there was an inverse association of maternal HEI with offspring insulin (%change −12.0; 95% CI −21.9, −0.9) and a positive association with 1/insulin (%change −13.6; 95% CI 0.9, 28.0) and LDL (5.45; 95% CI 0.90, 9.99) in unadjusted models. All estimates were attenuated to the null after accounting for covariates (Table 3, Models 1–3). ESM Fig. 2 shows correlations among the biomarkers and adiposity indicators among offspring at 4–7 years. Insulin was positively correlated with %FM and negatively correlated with adiponectin within boys and girls. Among boys, adiponectin was negatively correlated with BMI z score, whereas among girls adiponectin was positively correlated with %FM and BMI z score.

Sensitivity analyses

The mean HEI score in early pregnancy (N = 682) was 61.1 (10.1) and in late pregnancy (N = 441) was 63.0 (10.3). Among women who had data at both time-points (N = 424), the mean HEI score in early pregnancy was 62.3 (9.9) and in late pregnancy was 63.2 (10.3), with a global mean change of 0.03 (0.18) and a percentage change of 1.5%. HEI scores were positively correlated in early and late pregnancy (Pearson correlation: 0.46; p < 0.001). In analyses of early and late pregnancy HEI scores, each assessed separately as predictors of the offspring outcomes, we found consistent direction and magnitude of associations (albeit attenuated to the null due in part to the reduced sample size), including the inverse association between HEI score and biomarkers of glucose–insulin homeostasis among boys only (ESM Table 6). Additionally, findings were similar when we assessed associations of having consistently high HEI score (>57) across early and late pregnancy with offspring outcomes.

When controlling for total maternal kilocalories (tested in Model 2), we found no substantial change, such that HEI remained significantly associated with glucose (p = 0.02), insulin (p = 0.02), 1/insulin (p = 0.02), HOMA-IR (p = 0.03), adiponectin (p = 0.01) and TAGs:HDL ratio (p = 0.03) among boys and there were no significant associations among girls. Excluding women with GDM slightly attenuated the estimates and reduced statistical significance, with some evidence for a greater impact on insulin-based metrics. However, the overall trend in direction of association across all outcomes remained unchanged.

Discussion

Using longitudinal data collected in 761 mother–child pairs from gestation to early childhood, we examined associations of maternal diet quality during pregnancy, as measured by the HEI, with a panel of metabolic biomarkers and measures of body composition among offspring 4–7 years of age. Higher maternal diet quality during pregnancy was associated with a more favourable glucose–insulin homeostasis and lipid profile in male offspring, as indicated by lower concentrations of glucose, insulin and HOMA-IR, and the ratio of TAGs:HDL, even after accounting for potential confounders and mediators. Maternal HEI score was not associated with metabolic biomarkers or body composition among girls after accounting for maternal and perinatal characteristics.

In the present analysis, we found that already at 5 years of age, sex dimorphisms in markers of glucose–insulin homeostasis and body composition were detectable. Our most noteworthy finding is the apparent protective effect of higher maternal diet quality on the glucose–insulin homeostasis and lipid profile of boys. Interestingly, higher maternal diet quality was associated with lower levels of adiponectin in boys. Among adults, lower adiponectin is often associated with worse metabolic outcomes such as type 2 diabetes [48]. Prior studies in neonates and children have found positive associations of adiponectin with weight, weight gain and sum of skinfolds in childhood [49,50,51]. However, in childhood and during periods of rapid development (e.g., 4–7 years of age), the role of adiponectin is less clear. Indeed, in the current study, we found that among boys adiponectin was inversely associated with BMI z score and among girls it was positively associated with BMI z score. Although the exact roles of adipokines in early childhood are unknown and warrant future study, adiponectin may play a role in weight gain during early childhood that differs by sex. Thus, our findings of higher diet quality in pregnancy and lower offspring adiponectin may represent a protective process by which a healthful diet in pregnancy reduces risk for later increased weight gain in boys.

To date, most studies that examined maternal diet quality via the HEI, or HEI adaptations, assessed associations with outcomes at birth [11, 12, 42, 52, 53]. In general, our findings in male offspring align with existing literature documenting inverse associations of maternal HEI score with neonatal FM [11, 42], and markers of insulin resistance in cord blood [52], though sex-specific estimates were not reported. For instance, in a study among 35 Spanish mother–offspring pairs, low maternal diet quality in the first trimester was associated with higher glucose, insulin and HOMA-IR in cord blood [12]. However, not all studies have found associations with offspring metabolic health, either at birth [53] or in early childhood [8]. In addition, interpretations across studies should be considered cautiously given differences in participant demographics and cultural practices [12, 52], timing of offspring outcome assessment (birth vs childhood) and use of birthweight as a marker of metabolic risk.

The lower atherosclerotic and glycaemic components of the HEI diet [54] may influence fetal programming of metabolism and glucose homeostasis [55, 56] and increase susceptibility to metabolic traits in childhood. In the current study, despite no difference in the diet quality of women who delivered male vs female offspring, maternal diet was associated with offspring metabolic traits in a sex-specific manner. Data from animal models indicate that males are more susceptible to overnutrition in the gestational period and early life, which may arise from the effects of hormones, epigenetics and differences in placental size, shape and efficiency [6, 21, 57, 58]. Further, studies of the epigenome and transcriptome of murine and human placentas have shown clear sex-specific differences in gene expression with respect to maternal diet during pregnancy [22,23,24]. The ability of the placenta to adapt to changes in the maternal–fetal milieu [59] may contribute to the sex-specificity of our findings. A prevailing hypothesis is that male fetuses respond to the maternal milieu with fewer functional changes in the placenta, resulting in persistent fetal growth and development, regardless of whether that environment is optimal or substandard. In contrast, female fetuses show greater placental adaptation to maternal exposures, resulting in greater placental gene and protein changes and increased survival rate when confronted with adverse events such as nutrient deprivation [59,60,61]. Thus, it may be that the placentas of female fetuses are less impacted by the maternal environment, whether positively or negatively; and, while male fetuses demonstrate fewer adaptations, their increased sensitivity to maternal exposures results in greater receipt of benefits when, for instance, a healthy dietary pattern is consumed. However, this latter concept is speculative, and the underlying mechanisms are still under investigation.

Maternal HEI and offspring body composition

In the current study we did not find associations between maternal diet quality and offspring body composition. Prior studies have reported an inverse association of HEI with neonatal adiposity and birthweight [11, 12, 42, 62]. One study that followed offspring into adolescence and adulthood (ages 12–23 years) reported no association of HEI with risk of obesity during any time-period [63]. This could suggest that the effect of diet quality in pregnancy on offspring adiposity may diminish with increasing age. One potential explanation for our relatively null findings between maternal diet quality and early childhood adiposity is increased intra- and inter-individual variability in body composition during these transitional years. Continued follow-up will allow us to assess growth trajectories of participants as they age to shed light on this hypothesis.

Limitations of the data

We measured the HEI, which was designed to reflect the USA Dietary Guidelines, and thus our findings are likely more generalisable to women in the USA. The calculation of the HEI was based on data from dietary recalls collected over the course of pregnancy, which may suffer recall bias. However, this method of dietary assessment is considered valid to estimate relative dietary intake in large studies (and, therefore, inter-individual rank is preserved). On average, slightly more recalls were completed in the second and third trimesters (i.e., mean of 3.7 recalls during the first trimester, 3.8 recalls during the second trimester and 4.4 recalls during the third trimester) and thus our findings may reflect the effect of dietary quality in these time-periods. We provided a series of sequentially adjusted multivariable models that account for maternal and child confounders, mediators and lifestyle factors. Although these adjustments did attenuate some estimates, the association of higher maternal diet quality with markers of glucose–insulin homeostasis among boys remained significant.

Conclusions and future directions

In the current study, higher maternal diet quality during pregnancy was associated with a more favourable glucose–insulin homeostasis and lipid profile in male offspring. Future studies focused on identifying dietary intake thresholds among pregnant women should explore numerous cut-offs and consider whether thresholds are specific to the outcome of interest, i.e., offspring health vs maternal health. There are many mediating lifestyle factors that link maternal diet to offspring health which could be points of intervention, and which warrant further exploration in future analyses. The onset of childhood obesity and associated metabolic traits are occurring at increasingly early ages [64, 65], highlighting the gestational period as a critical window during which prevention efforts could have long-lasting impacts. The relevance of sex in susceptibility to and severity of disease is highly complex, and whether a particular sex has a more appropriate response to diet quality during gestation that persists into adulthood is likely dependent on myriad factors [58]. Given that pregnancy represents a window of opportunity for change that may result in sustained healthy behaviours for both mother and child, increased emphasis on adherence to dietary patterns during pregnancy that align with the HEI and USA Dietary Guidelines may improve the maternal–fetal milieu.

Data availability

Data described in the manuscript, code book and analytic code will be made available upon request pending reasonable application and approval.

Abbreviations

- ASA24:

-

Automated Self-Administered 24-h Dietary Recall

- FM:

-

Fat mass

- %FM:

-

Percentage fat mass

- GA:

-

Gestational age

- GDM:

-

Gestational diabetes mellitus

- HEI:

-

Healthy Eating Index-2010

- TAG:

-

Triacylglycerol

References

Perng W, Oken E (2017) Chapter 15 - Programming Long-Term Health: Maternal and Fetal Nutrition and Diet Needs. In: Saavedra JM, Dattilo AM (eds) Early Nutrition and Long-Term Health. Woodhead Publishing, Sawston, UK, pp 375–411

Hu FB (2002) Dietary pattern analysis: a new direction in nutritional epidemiology. Curr Opin Lipidol 13(1):3–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/00041433-200202000-00002

Shivappa N, Steck SE, Hurley TG, Hussey JR, Hébert JR (2014) Designing and developing a literature-derived, population-based dietary inflammatory index. Public Health Nutr 17(8):1689–1696. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980013002115

Guenther PM, Kirkpatrick SI, Reedy J et al (2014) The Healthy Eating Index-2010 is a valid and reliable measure of diet quality according to the 2010 Dietary Guidelines for Americans. J Nutr 144(3):399–407. https://doi.org/10.3945/jn.113.183079

Trichopoulou A, Costacou T, Bamia C, Trichopoulos D (2003) Adherence to a Mediterranean diet and survival in a Greek population. N Engl J Med 348(26):2599–2608. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa025039

Sen S, Rifas-Shiman SL, Shivappa N et al (2018) Associations of prenatal and early life dietary inflammatory potential with childhood adiposity and cardiometabolic risk in Project Viva. Pediatr Obes 13(5):292–300. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijpo.12221

Chatzi L, Rifas-Shiman SL, Georgiou V et al (2017) Adherence to the Mediterranean diet during pregnancy and offspring adiposity and cardiometabolic traits in childhood. Pediatr Obes 12(Suppl 1):47–56. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijpo.12191

Leermakers ETM, Tielemans MJ, van den Broek M, Jaddoe VWV, Franco OH, Kiefte-de Jong JC (2017) Maternal dietary patterns during pregnancy and offspring cardiometabolic health at age 6 years: The generation R study. Clin Nutr 36(2):477–484. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2015.12.017

Dhana K, Zong G, Yuan C et al (2018) Lifestyle of women before pregnancy and the risk of offspring obesity during childhood through early adulthood. Int J Obes 42(7):1275–1284. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41366-018-0052-y

Zhu Y, Hedderson MM, Sridhar S, Xu F, Feng J, Ferrara A (2019) Poor diet quality in pregnancy is associated with increased risk of excess fetal growth: a prospective multi-racial/ethnic cohort study. Int J Epidemiol 48(2):423–432. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyy285

Tahir MJ, Haapala JL, Foster LP et al (2019) Higher Maternal Diet Quality during Pregnancy and Lactation Is Associated with Lower Infant Weight-For-Length, Body Fat Percent, and Fat Mass in Early Postnatal Life. Nutrients 11(3):632. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11030632

Chia AR, Tint MT, Han CY et al (2018) Adherence to a healthy eating index for pregnant women is associated with lower neonatal adiposity in a multiethnic Asian cohort: the Growing Up in Singapore Towards healthy Outcomes (GUSTO) Study. Am J Clin Nutr 107(1):71–79. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/nqx003

Günther J, Hoffmann J, Spies M et al (2019) Associations between the prenatal diet and neonatal outcomes-a secondary analysis of the cluster-randomised gelis trial. Nutrients 11(8). https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11081889

Stefan N, Schick F, Häring H-U (2017) Causes, Characteristics, and Consequences of Metabolically Unhealthy Normal Weight in Humans. Cell Metab 26(2):292–300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2017.07.008

Henderson M, Van Hulst A, von Oettingen JE, Benedetti A, Paradis G (2019) Normal weight metabolically unhealthy phenotype in youth: Do definitions matter? Pediatr Diabetes 20(2):143–151. https://doi.org/10.1111/pedi.12785

Shank LM, Neyland MKH, Lavender JM et al (2020) Sex differences in metabolic syndrome components in adolescent military dependents at high-risk for adult obesity. Pediatr Obes 15(8):9. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijpo.12638

Guzzetti C, Ibba A, Casula L, Pilia S, Casano S, Loche S (2019) Cardiovascular Risk Factors in Children and Adolescents With Obesity: Sex-Related Differences and Effect of Puberty. Front Endocrinol 10:591. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2019.00591

Dearden L, Bouret SG, Ozanne SE (2018) Sex and gender differences in developmental programming of metabolism. Mol Metab 15:8–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molmet.2018.04.007

Eriksson JG, Kajantie E, Osmond C, Thornburg K, Barker DJP (2010) Boys live dangerously in the womb. Am J Hum Biol 22(3):330–335. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajhb.20995

Regnault N, Gillman MW, Rifas-Shiman SL, Eggleston E, Oken E (2013) Sex-specific associations of gestational glucose tolerance with childhood body composition. Diabetes Care 36(10):3045–3053. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc13-0333

Ainge H, Thompson C, Ozanne SE, Rooney KB (2011) A systematic review on animal models of maternal high fat feeding and offspring glycaemic control. Int J Obes 35(3):325–335. https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2010.149

Sedlmeier EM, Brunner S, Much D et al (2014) Human placental transcriptome shows sexually dimorphic gene expression and responsiveness to maternal dietary n-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acid intervention during pregnancy. BMC Genomics 15(1):941. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2164-15-941

Mao J, Zhang X, Sieli PT, Falduto MT, Torres KE, Rosenfeld CS (2010) Contrasting effects of different maternal diets on sexually dimorphic gene expression in the murine placenta. Proc Natl Acad Sci 107(12):5557–5562. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1000440107

Gabory A, Ferry L, Fajardy I et al (2012) Maternal diets trigger sex-specific divergent trajectories of gene expression and epigenetic systems in mouse placenta. PLoS One 7(11):e47986. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0047986

Guenther PM, Casavale KO, Reedy J et al (2013) Update of the Healthy Eating Index: HEI-2010. J Acad Nutr Diet 113(4):569–580. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jand.2012.12.016

Anderson PM, Butcher KF, Schanzenbach DW (2019) Understanding recent trends in childhood obesity in the United States. Econ Hum Biol 34:16–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ehb.2019.02.002

Hruby A, Hu FB (2015) The Epidemiology of Obesity: A Big Picture. Pharmacoeconomics 33(7):673–689. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-014-0243-x

Subar AF, Kirkpatrick SI, Mittl B et al (2012) The Automated Self-Administered 24-hour dietary recall (ASA24): a resource for researchers, clinicians, and educators from the National Cancer Institute. J Acad Nutr Diet 112(8):1134–1137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jand.2012.04.016

Guenther PM, Reedy J, Krebs-Smith SM, Reeve BB, Basiotis PP (2007) Development and Evaluation of the Healthy Eating Index-2005: Technical Report. Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion, U.S. Department of Agriculture. Available from https://www.fns.usda.gov/cnpp/healthy-eating-index-hei-reports. Accessed Jun 2021

Fields DA, Allison DB (2012) Air-Displacement Plethysmography Pediatric Option in 2–6 Years Old Using the Four-Compartment Model as a Criterion Method. Obesity 20(8):1732–1737. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2012.28

World Health Organizaton (2006) WHO child growth standards: height-for-age, weight-for-age, weight-for-length, weight-for-height and body mass index for-age: methods and development. World Health Organizaton, Geneva, Switzerland

de Onis M, Garza C, Victora C, Bhan M, Norum K (2004) The WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study (MGRS): rationale, planning, and implementaton. Food Nutr Bull 25(Suppl 1):S1–S89

Urbina EM, Khoury PR, McCoy CE, Dolan LM, Daniels SR, Kimball TR (2013) Triglyceride to HDL-C ratio and increased arterial stiffness in children, adolescents, and young adults. Pediatrics 131(4):e1082–e1090. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2012-1726

McLaughlin T, Abbasi F, Cheal K, Chu J, Lamendola C, Reaven G (2003) Use of metabolic markers to identify overweight individuals who are insulin resistant. Ann Intern Med 139(10):802–809. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-139-10-200311180-00007

Singh B, Saxena A (2010) Surrogate markers of insulin resistance: A review. World J Diabetes 1(2):36–47. https://doi.org/10.4239/wjd.v1.i2.36

Levy JC, Matthews DR, Hermans MP (1998) Correct homeostasis model assessment (HOMA) evaluation uses the computer program. Diabetes Care 21(12):2191–2192. https://doi.org/10.2337/diacare.21.12.2191

Chasan-Taber L, Schmidt MD, Roberts DE, Hosmer D, Markenson G, Freedson PS (2004) Development and validation of a Pregnancy Physical Activity Questionnaire. Med Sci Sports Exerc 36(10):1750–1760. https://doi.org/10.1249/01.MSS.0000142303.49306.0D

Rowlands AV (2007) Accelerometer assessment of physical activity in children: an update. Pediatr Exerc Sci 19(3):252–266. https://doi.org/10.1123/pes.19.3.252

van Cauwenberghe E, Labarque V, Trost SG, de Bourdeaudhuij I, Cardon G (2011) Calibration and comparison of accelerometer cut points in preschool children. Int J Pediatr Obes 6(2–2):e582–e589. https://doi.org/10.3109/17477166.2010.526223

Rifas-Shiman SL, Rich-Edwards JW, Willett WC, Kleinman KP, Oken E, Gillman MW (2006) Changes in dietary intake from the first to the second trimester of pregnancy. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 20(1):35–42. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3016.2006.00691.x

Hinkle SN, Zhang C, Grantz KL et al (2021) Nutrition during Pregnancy: Findings from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) Fetal Growth Studies-Singleton Cohort. Curr Dev Nutr 5(1):nzaa182. https://doi.org/10.1093/cdn/nzaa182

Shapiro ALB, Kaar JL, Crume TL et al (2016) Maternal diet quality in pregnancy and neonatal adiposity: the Healthy Start Study. Int J Obes 40(7):1056–1062. https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2016.79

Food and Nutrition Service (2019) HEI Scores for Americans. Available from https://www.fns.usda.gov/hei-scores-americans. Accessed 27 Oct 2020

Schulz KF, Grimes DA (2005) Multiplicity in randomised trials I: endpoints and treatments. Lancet 365(9470):1591–1595. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(05)66461-6

Westfall PH, Young S (1993) Resampling-based multiple testing: examples and methods for p-value adjustment. Wiley, Hoboken, NJ, USA ISBN: 978-0-471-55761-6

SAS Institute (2020) The MULTTEST Procedure. Available from https://documentation.sas.com/?cdcId=pgmsascdc&cdcVersion=9.4_3.4&docsetId=statug&docsetTarget=statug_multtest_overview.htm&locale=en. Accessed 6 Nov 2020

Basiotis PP, Carlson A, Gerrior SA, Juan WY, Lino M (2004) Healthy Eating Index, 1999-2000: charting dietary patterns of Americans. Fam Econ Nutr Rev 16(1):39–48

Gao H, Fall T, van Dam RM et al (2013) Evidence of a Causal Relationship Between Adiponectin Levels and Insulin Sensitivity. Diabetes 62(4):1338. https://doi.org/10.2337/db12-0935

Yeung EH, Sundaram R, Xie Y, Lawrence DA (2018) Newborn adipokines and early childhood growth. Pediatr Obes 13(8):505–513. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijpo.12283

Parker M, Rifas-Shiman SL, Belfort MB et al (2011) Gestational glucose tolerance and cord blood leptin levels predict slower weight gain in early infancy. J Pediatr 158(2):227–233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.07.052

Nakano Y, Itabashi K, Nagahara K et al (2012) Cord serum adiponectin is positively related to postnatal body mass index gain. Pediatr Int 54(1):76–80. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1442-200X.2011.03521.x

Gesteiro E, Rodríguez Bernal B, Bastida S, Sánchez-Muniz FJ (2012) Maternal diets with low healthy eating index or Mediterranean diet adherence scores are associated with high cord-blood insulin levels and insulin resistance markers at birth. Eur J Clin Nutr 66(9):1008–1015. https://doi.org/10.1038/ejcn.2012.92

Rifas-Shiman SL, Rich-Edwards JW, Kleinman KP, Oken E, Gillman MW (2009) Dietary quality during pregnancy varies by maternal characteristics in Project Viva: a US cohort. J Am Diet Assoc 109(6):1004–1011. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jada.2009.03.001

Chiuve SE, Fung TT, Rimm EB et al (2012) Alternative Dietary Indices Both Strongly Predict Risk of Chronic Disease. J Nutr 142(6):1009–1018. https://doi.org/10.3945/jn.111.157222

Nolan CJ, Prentki M (2019) Insulin resistance and insulin hypersecretion in the metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes: Time for a conceptual framework shift. Diab Vasc Dis Res 16(2):118–127. https://doi.org/10.1177/1479164119827611

McCurdy CE, Bishop JM, Williams SM et al (2009) Maternal high-fat diet triggers lipotoxicity in the fetal livers of nonhuman primates. J Clin Invest 119(2):323–335. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI32661

Elahi MM, Cagampang FR, Mukhtar D, Anthony FW, Ohri SK, Hanson MA (2009) Long-term maternal high-fat feeding from weaning through pregnancy and lactation predisposes offspring to hypertension, raised plasma lipids and fatty liver in mice. Br J Nutr 102(4):514–519. https://doi.org/10.1017/s000711450820749x

Gabory A, Vige A, Ferry L et al (2014) Male and Female Placentas Have Divergent Transcriptomic and Epigenomic Responses to Maternal Diets: Not Just Hormones. In: Seckl JR, Christen Y (eds) Hormones, Intrauterine Health and Programming, vol 12. Springer, New York, NY, USA, pp 71–91

Tarrade A, Panchenko P, Junien C, Gabory A (2015) Placental contribution to nutritional programming of health and diseases: epigenetics and sexual dimorphism. J Exp Biol 218(1):50–58. https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.110320

Burton GJ, Fowden AL, Thornburg KL (2016) Placental Origins of Chronic Disease. Physiol Rev 96(4):1509–1565. https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.00029.2015

Clifton VL (2010) Review: Sex and the Human Placenta: Mediating Differential Strategies of Fetal Growth and Survival. Placenta 31:S33–S39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.placenta.2009.11.010

Chia A-R, Chen L-W, Lai JS et al (2019) Maternal Dietary Patterns and Birth Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Adv Nutr 10(4):685–695. https://doi.org/10.1093/advances/nmy123

Strohmaier S, Bogl LH, Eliassen AH et al (2020) Maternal healthful dietary patterns during peripregnancy and long-term overweight risk in their offspring. Eur J Epidemiol 35(3):283–293. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-020-00621-8

Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Lawman HG et al (2016) Trends in Obesity Prevalence Among Children and Adolescents in the United States, 1988-1994 Through 2013-2014. JAMA 315(21):2292–2299. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.6361

Mayer-Davis EJ, Lawrence JM, Dabelea D et al (2017) Incidence Trends of Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes among Youths, 2002-2012. N Engl J Med 376(15):1419–1429. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1610187

Acknowledgements

We thank the Healthy Start II participants, as well as past and present research assistants.

Authors’ relationships and activities

The authors declare that there are no relationships or activities that might bias, or be perceived to bias, their work.

Funding

This study was funded by 5R01DK076648-10. ECF is supported by the T32 fellowship granted to the University of Colorado from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (5T32HD007186-39). WP is supported by the Center for Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute (CCTSI) (KL2-TR002534).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KS and DD conceived the research question. ECF conducted the analysis, wrote the initial draft of the paper and incorporated co-author comments. WP provided critical feedback on the analysis. KS, DD and WP contributed to data interpretation and reviewed the manuscript. All co-authors approved the final version of the paper. ECF and WP are the guarantors of this work and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

ESM

(PDF 513 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Francis, E.C., Dabelea, D., Shankar, K. et al. Maternal diet quality during pregnancy is associated with biomarkers of metabolic risk among male offspring. Diabetologia 64, 2478–2490 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-021-05533-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-021-05533-0