(This is a reprint of an art history paper written for London Art College)

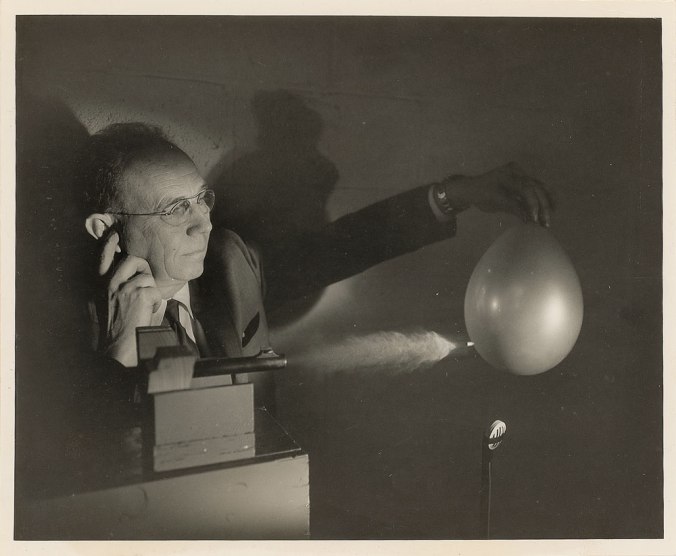

The item for my last paper is the above original 1959 stroboscopic photograph of Harold Edgerton holding a balloon with a bullet being fired at it. The back has the original information sheet from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). I pick the photograph because it involved a new way to look at the world and because it touches on the questions of what is art. Edgerton did not consider himself be to an artist nor his photos to be artworks, but many collect his photos as artworks and they are hung in art museums.

Harold Edgerton was an American professor of electrical engineering at MIT who became world famous for his invention of the strobe light (the basis for today’s flash photography) and stroboscopic photography. The latter is a form of ultra high speed photography using strobe lights. This image was photographed at 1/2,000,000th of a second.

Edgerton was studying turbine engines in his 1930s Cambridge Massachusetts lab and wanted clear stop-action images of the engines in motion. However, camera systems of the day could not take such high speed photographs because their shutters opened and closed too slowly. A turbine is many times faster than a camera shutter. Instead of ‘clicking’ photos of high speed objects, Edgerton’s new process turned off the lights, opened wide the camera’s shutter and, in the darkness, shot quick flashes of light from his strobe light onto the moving subject. The camera film would thus show a series of instantaneous and frozen-in-time shots of action.

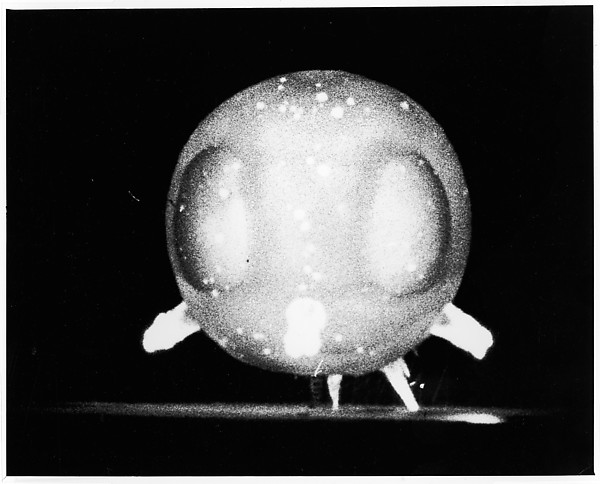

At the advice of a student, Edgerton started taking stroboscopic photographs of everyday objects and revealed a world never before seen by human eyes. He showed still, unblurred images of things that move far too fast to be clearly perceived by human eyes. This included speeding bullets, hummingbirds’ wings in mid flap, atomic explosions, smashing glass, the swing of a golf club and the splash of a milk drop.

atomic explosion

Woman with her pet humming birds

Not only were these photographs scientifically revealing and important– and that was Edgerton’s purpose–, but non-scientists found them fascinating, sometimes beautiful and some were even considered to be works works of art. His photographs are auctioned by Sotheby’s and Christie’s and exhibited by museums including the Museum of Modern Art. Many people I asked consider some of his most famous photos to be art.

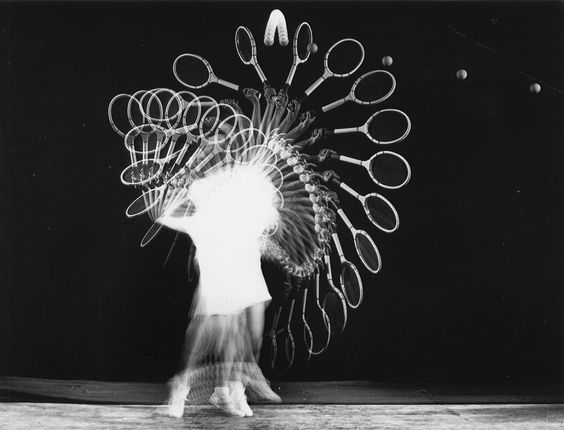

Though intended and used by Edgerton as a purely scientific device, his novel technique can be compared to historical novel artistic methods of looking at and depicting the world, including the ‘blurry’ brushwork and colors of impressionism, John Constable’s use of color and brushwork to better depict reality, Caravaggio’s use of lighting, pose and hyper reality to depict scenes in a new and visceral way. Some stroboscopic photos reveal the subject in a series of snapshots, closely resembling Marcel Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2. (See the later shown Edgerton photo of a tennis player and Elliot Elisofon’s 1952 stroboscopic photo of Marcel Duchamp descending stairs).

All these novel techniques expand our minds and view of the world, give us more information about the subjects and give us new aesthetic experiences. The novelty alone produces an aesthetic and emotional reaction (sometimes good, sometimes bad). Edgerton said the photos often revealed unexpected results and details. Science– and Edgerton considered his photos to be science– can expand our minds and give us wonder similar to art. Pure mathematicians often say they get an aesthetic and sublime emotional response to doing their work– though they also say accurate results always trump beauty.

Tennis player by Edgerton

Duchamp descending stairs by Elisofon

Not only do many consider some of Edgerton’s photographs to be beautiful, but they often find them profound and inspiring as they reveal a once secret world that happens beneath our very noses. Many may find the images bring up philosophic topics of time, reality and perception, and perhaps give religious inspiration (‘God’s details’).

Others may not consider them art, but still find them fascinating and worthy of hanging on a wall– or at least taping to the refrigerator door. Some may call them eye candy not art, but, as I say about movies, there’s nothing wrong with wanting to be entertained. I think Edgerton’s photos are fascinating, but more eye candy than art. Though I also know art is subjective and if a viewer considers them metaphysically and emotionally profound, I won’t argue with them.

What is particularly interesting is Edgerton firmly called himself a scientist not an artist and, while he no doubt found many of the images striking and even beautiful, did not consider them artworks. He said “Don’t make me out to be an artist. I am an engineer. I am after the facts. Only the facts.”

If people call his photos artworks, it had nothing to do with his intent or design. In fact, I bet he would have said that, as a scientist doing scientific tests, thinking about about making them artistic would be dangerous. Predetermined results, aesthetic aims, trying to get final results that are pretty and pleasing to the senses and emotions makes for bad science. That some of the photos came out aesthetically pleasing and would look nice hung on a wall were fine, but Edgerton thought the aesthetics to be beside the point and the focus on it dangerous to his work.

Further, not all of this photos are considered ‘art’ and this gets into the nature of why people consider some things art and other things not. Some of this photos are fairly ugly or mundane, if still fascinating. I picked the 1959 photo in part because it is not terribly attractive. Interesting but not ‘beautiful.’

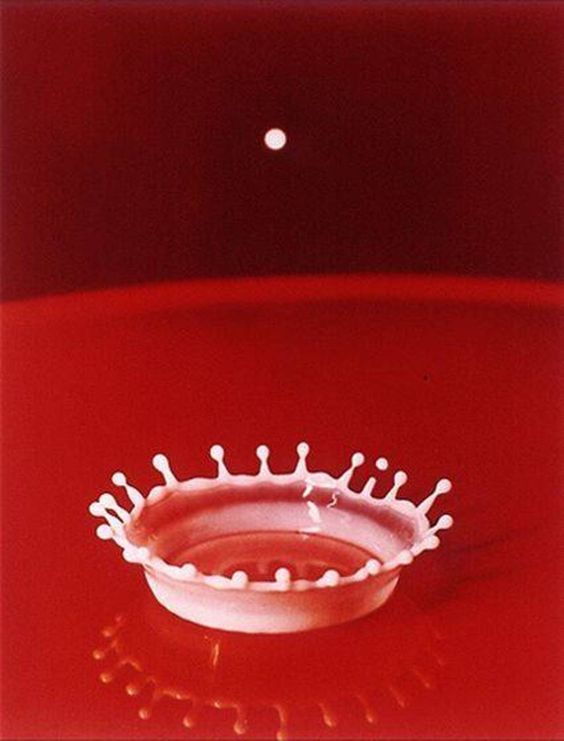

I showed a friend two Edgerton photos: his famous milkdrop photo (shown below) and this original 1959 photo. She said the milkdrop photo was art, but not the 1959 photo. They are both similar high speed photos, so how is one considered art and one not? Because one was ‘beautiful’ or aesthetically pleasing to her taste and the other was not. Her response was immediate. She didn’t have to mull it over or do research. Is the definition of what is art this superficial? Or was she mistaking eye candy for art? Is her seeming superficiality and gut emotional reaction an example of why Edgerton, the scientist doing scientific work, had a clinical distaste of the word artist and art?

Edgerton’s Milk drop

As discussed in my earlier papers on Renoir, Kandinsky and the article on neuroaesthics, some neurobiologists believe that our aesthetic and emotional reactions to art and nature is in major part based in hard wired neurological reactions to basic qualities. The viewer’s wonder, awe and attracted attention at the novelty of the above image is natural and evolutionary, as is the emotional pleasingness of the symmetry, colors and ‘texture.’ The neurobiologists would say it is natural that the simple, balanced milk drop photo is more aesthetically pleasing than the dark, muddled 1959 photo.

While it was a scientific device for Edgerton, other photographers intentionally used his high speed techniques for artistic purposes. Famed Life magazine photographer Gjon Mili was the first photographer to use the techniques for aesthetic purposes. All modern art photographers who use flashes have Edgerton to thank.

‘Woman in raincoat’ (1941) by Gjon Mili

Edgerton was no dummy (MIT professors rarely are) and made high quality prints of his most beautiful images and sold them as signed limited edition works. These are what are sold at auction and displayed in museums. Whether or not this was a jaded money grab can be debated. He may have thought the photographs neat looking and, as a well known promoter of science to the general public, was happy to fill the public’s need for scientific eye candy.

Though not pretty, the 1959 photograph has value amongst some collectors, not as an artwork but as a historical artifact. Collectors of antique artifacts and memorabilia do not only collect objects of beauty but objects of historical or other non-art interest. Most of Edgerton’s signed and limited edition art photos were made years after the images were shot, and vintage original examples such as this are rare. Vintage original photos with Edgerton himself in the photo are even rarer. The 1959 photo was used as an ephemeral press release by M.I.T. and it was chance that it was not lost or thrown out over the years. It wasn’t until recent years that press, news and wire photos, some by famous photographers, became collectable and financially valuable.

If not art, this 1959 photograph would be desirable to collectors of science and history of photography memorabilia. That the back has the original M.I.T. tag on back makes it even more desirable to artifact collectors.

In fact, many collectors of historical artifacts would have no desire for the signed limited edition photos, because they are not vintage. They are history collectors who want artifacts from the period and might dismiss the later made art photos as reproductions. Some would scratch their heads why someone would pay good money for a photograph made years after the image was shot. A collector of American Civil War memorabilia wants a battle flag, sword or photograph from the time of the war, not a reproduction made one hundred years later. How attractive or physically accurate is the reproduction does not matter to them. For history collectors, age is an essential quality.

Due to the two types of collectors, the later made art photo and the ‘dingy’ but original 1959 photo have about the same financial value. One because it is a limited edition ‘work of art’ signed by the famous scientist and photographer, and the other because it is a rare historical artifact showing a rare scene. One could be displayed in an art museum and the other in a science and technology museum.